A direct outcome of demonetisation is a sharp increase in 2017-18 in tax buoyancy (revenues per unit of growth). Given this ‘unexpected’ result, will the knee-jerk critics of demonetisation please stand down?

One strong argument against the policy of demonetisation is that it has failed to achieve its goal of catching black money — and it has brought about a perceptible decline in GDP growth. In 2015-16, GDP growth averaged 8 per cent; in 2016-17, GDP growth was 7.1 per cent, and 2017-18, the CSO expectation is for an average of 6.5 per cent.

A 1.5 per cent lower growth rate is very close to the Congress’s claim that GDP growth would decline by two percentage points because of demonetisation. I don’t know if the negative growth effects of demonetisation were expected to persist for 17 months (demonetisation was announced on November 8, 2016, and fiscal year 2017/18 ends March 2018), but the correlation of the decline with demonetisation is pronounced.

Of course, there are other factors that could have led to the decline in the GDP growth rate. The “usual suspects” for growth decline include macro-economic imbalance, lack of adequate infrastructure, growing NPAs of banks, and an appreciating exchange rate.

All of these problems (except an appreciating exchange rate) were present in 2015-16. The nominal exchange rate did depreciate by 7 per cent in 2015-16 when the growth rate accelerated from 7.5 per cent to 8 per cent. However, in 2012-13, the exchange rate depreciated by 14 per cent (rupee/$ went from 54.4 to 60.4) and GDP growth rate declined from 6.6 to 5.5 per cent. Further, note that the average exchange rate in fiscal year 2017-18 is just 2 per cent higher than that which prevailed in the high-growth year, 2015-16.

There will be another occasion to discuss how much, and in what manner, the exchange rate affects GDP growth. For the moment, I just want to observe that no economist associated with the UPA government is mentioning, let alone pointing to, the major contributory cause to the lower growth rate in 2017-18 — the large increase in real repo rates to 3 per cent, the highest observed in India since 2003, and the third-highest among major countries in 2017-18 (behind Brazil and Russia). I want to go back to demonetisation.

Some economists (and their followers on Twitter) are unabashedly claiming that no “good” economist has supported the policy of demonetisation. Of course, this is an embarrassingly self-serving ideological view but we will let that pass for the moment. There are at least three realised short term “costs” to the policy of demonetisation: Costs of implementation (standing in queues etc.); all the money being returned into the system (no black money being caught red handed) and most importantly, a decline in the GDP growth rate (but that could also be due to exchange rate, infrastructure, NPAs, or real interest rates).

So what did India gain from demonetisation? Demonetisation was announced on November 8, 2016. In an article 11 days later, (‘Big Bang or Big Thud?’, IE, November 19, 2017), I wrote that a necessary condition for considering demonetisation a success would be a significant increase in direct tax compliance, that is, the tax revenue collected from individuals and firms should increase significantly.

In other articles over the last two years, I have discussed how circa 2013-14, personal tax compliance in India was a low 25 per cent, that is, the government was able to collect only 25 per cent of the money that was due (based on the tax schedule and income distribution). As comparison, in the US (IRS data), the government is able to collect 82 per cent of taxes due from households. In other words, if tax compliance were to increase, there would be considerable scope for revenue enhancement for a given unit of income (nominal GDP) growth.

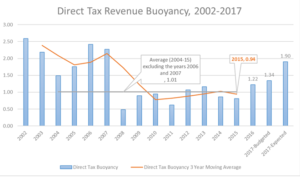

One measure of an increase in tax compliance is an increase in tax buoyancy. Buoyancy is conventionally defined as the ratio of percentage change in tax collection to percentage change in GDP, where the latter is a proxy for percentage change in personal pre-tax income. Direct tax compliance has averaged around unity for most of the years 2002-2014 (see chart). Note that in four of the early years (2002, 2003, 2006 and 2007), buoyancy was above 2, reflecting the increasing spread of taxation (more people being brought under the tax net) and increasing spread of TDS (tax deducted at source), as well as a rather robust growth in corporate profits.

Between 2009-10 and 2014-15, direct tax buoyancy averaged 0.93 — for each 10 per cent increase in GDP, direct tax collections rose by 9.3 per cent. From 2014, a time period during which the Modi government was very public about its “attack” on corruption and its efforts to increase tax compliance, until late 2016, tax buoyancy did not change much.

In 2015, direct tax buoyancy was the same as in 2014, a low 0.81. In demonetisation year 2016-17, direct tax buoyancy increased to 1.22. And based on data for three-quarters of the fiscal year 2017-18, tax buoyancy has jumped to 1.90 — the highest excluding the four exceptional years noted above (2002, 2003, 2006 and 2007).

At the time of presentation of the Budget 2017-18 (February 1, 2017), demonetisation was less than three-months-old, and its effects were highly uncertain. Yet, the Modi government pencilled in a large 15.7 per cent increase in direct tax revenues along with the expectation of an 11.75 per cent increase in nominal GDP, that is, an expected buoyancy of 1.34, a significant increase over the recent decadal average of unity.

However, nominal income only increased by 9.5 per cent (partly, or mostly, due to a very hard-line monetary policy). With the expected tax buoyancy of 1.34, direct tax revenues would have increased by 12.7 per cent, resulting in a direct tax revenue deficiency of Rs 26,000 crore in 2017-18. Now, with net direct tax revenues growing at an 18.2 per cent rate (April through December), rather than the budgeted 15.7 per cent rate, there should be close to Rs 20,000-crore surplus in direct tax collections. Net-net, the economy will have gained Rs 46,000 crore.

There is little reason to believe that the extra buoyancy is temporary. Rather, this is likely to be a permanent change in India’s fiscal landscape. The full implementation of GST should also enhance the buoyancy of both direct, and indirect, tax collections. If tax collection buoyancy is also reflected in GST collections, then the budget deficit for 2017-18 is likely to be close to the budgeted target of 3.2 per cent. And if that happens, will demonetisation critics say that perhaps it was good that no “good” economist endorsed demonetisation?