summary

Kashmir’s Internet Siege provides an overview of the harms, costs and consequences of the digital siege in Jammu & Kashmir, from August 2019 to the publication of this report in August 2020. We examine the shutdown and network disruptions through a broad-based and multi- dimensional human rights framework that sees internet access as vital in the contemporary world.

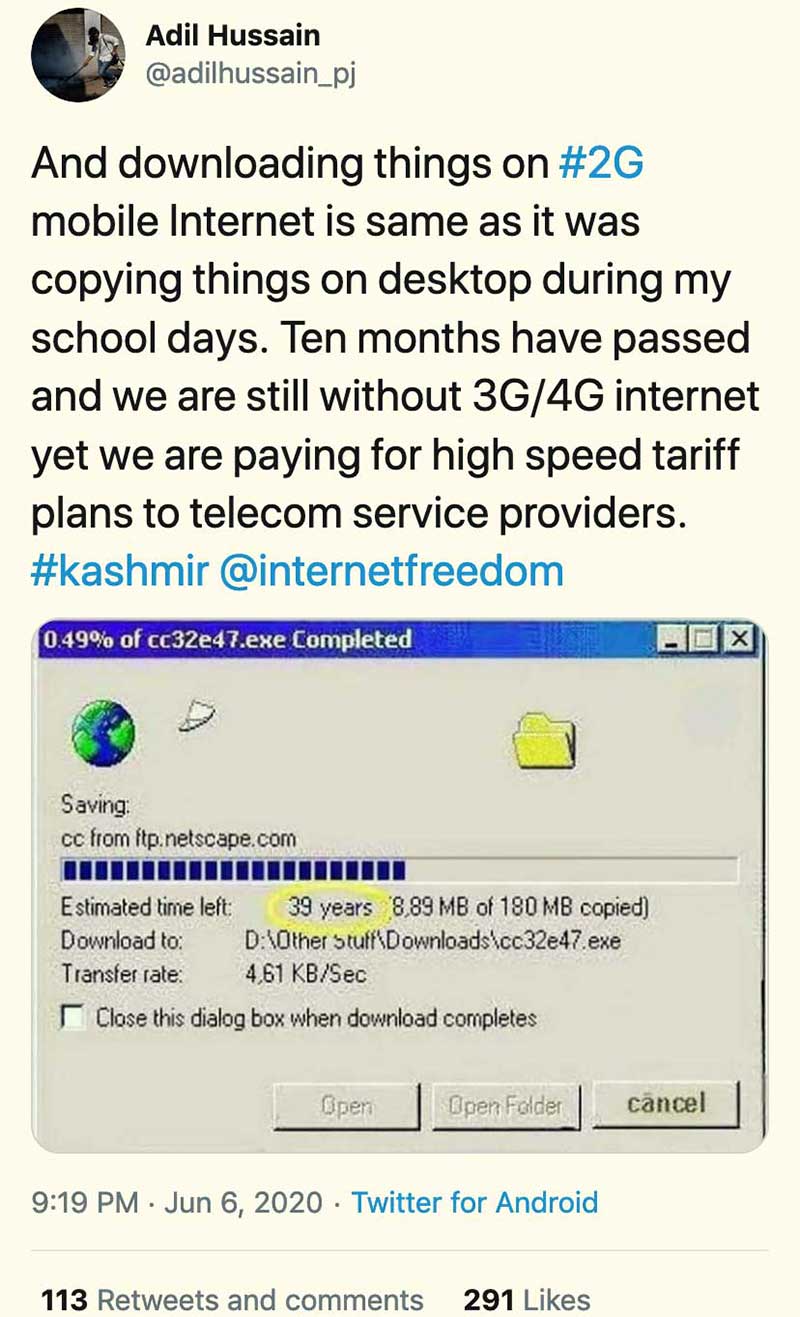

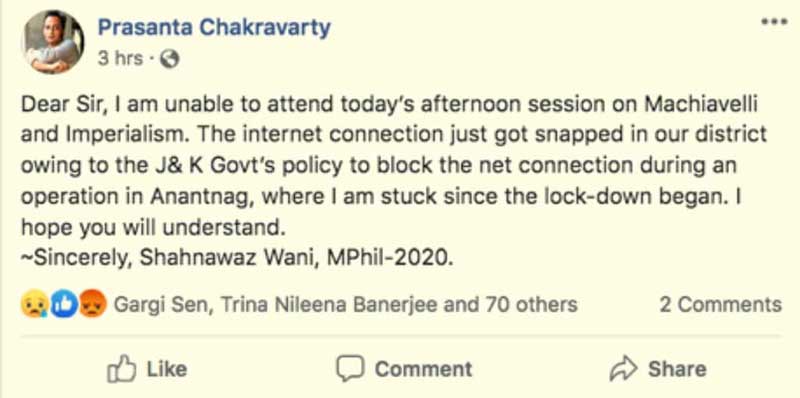

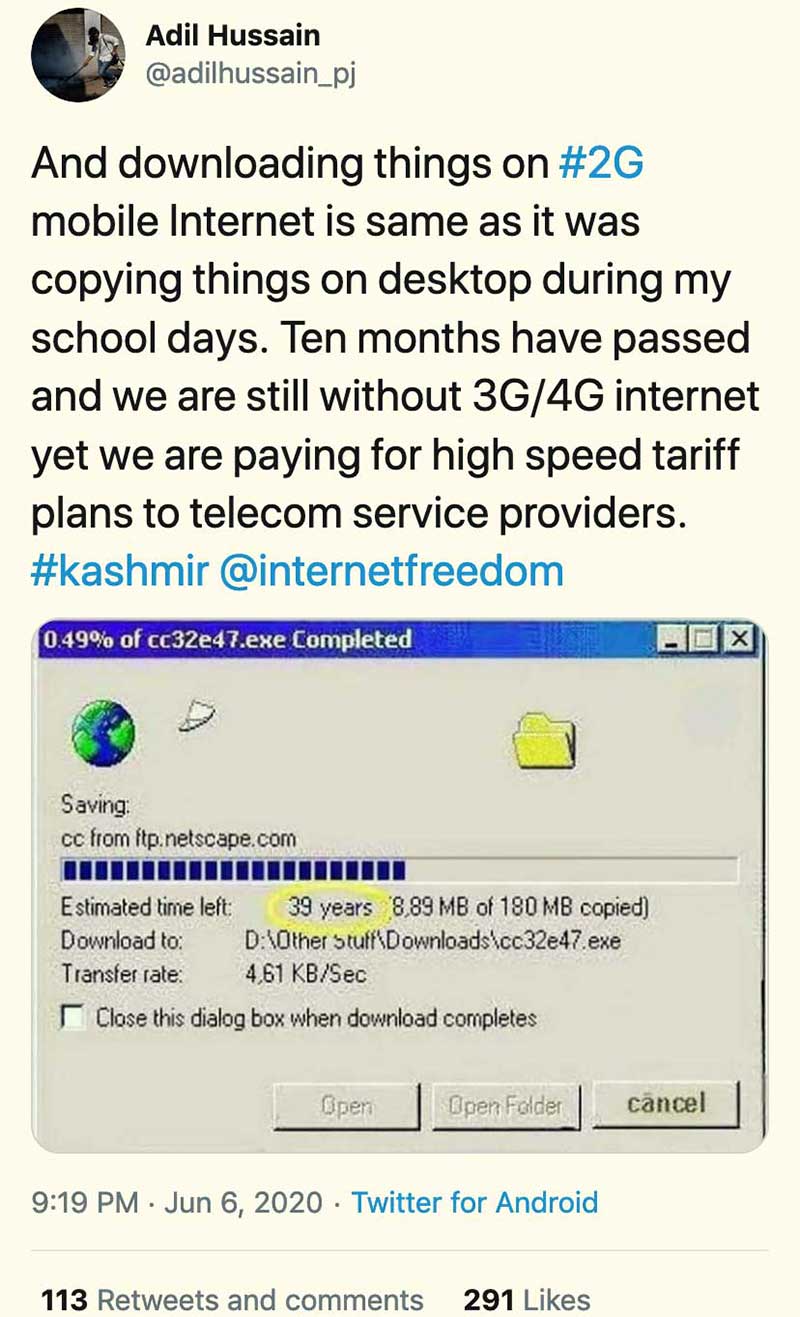

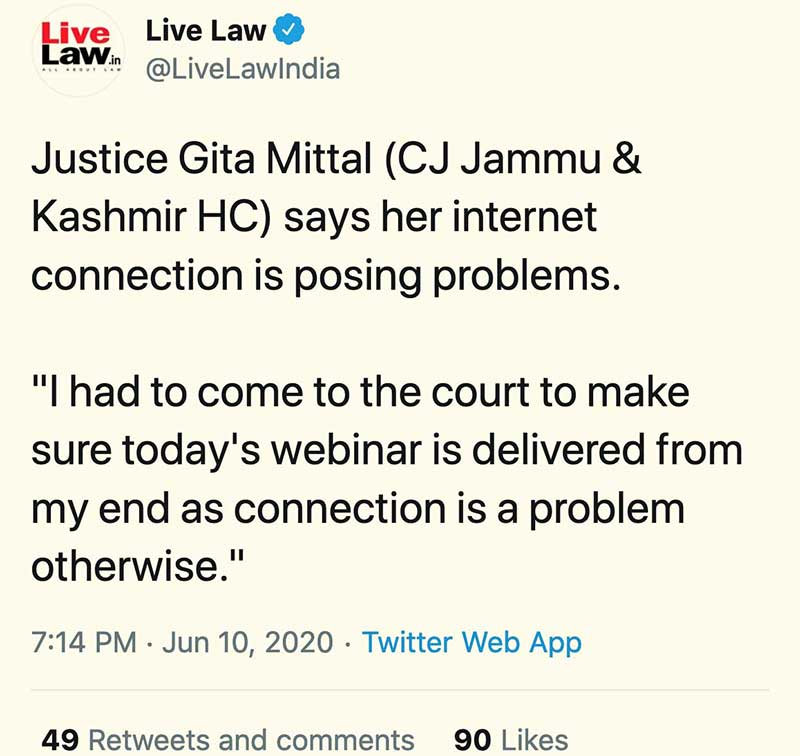

India leads the world in ordering internet shutdowns, and both in terms of frequency and duration, Jammu & Kashmir accounts for more than two-thirds of the Indian shutdowns ordered. Mobile internet data speed in Kashmir is currently restricted to 2G internet (250kbps). Even this access remains extremely precarious as localized shutdowns of the internet in specific districts or areas, often accompanied by mobile phone disruptions, are commonplace, sometimes lasting for upto a week.

In this report we contextualise the digital siege in light of long standing, widespread and systematic patterns of rights violations in Kashmir. Digital sieges are a technique of political repression in Kashmir, and a severe impediment to the enjoyment of internationally and constitutionally guaranteed civil, political and socio-economic rights. They curtail circulation of news and information, restrict social and emergency communications, and silence and criminalise all forms of political interactions and mobilisations as "militancy related" "terrorist activity" and threats to "national security".

The Background to the report discusses the legal framework and judicial precedents relating to the denial of digital rights in Kashmir, premised on militarised national security policies and practices. Internet shutdowns and restrictions in Kashmir also raise important questions of collective punishment in the context of an ongoing armed conflict, where the framework of international humanitarian laws applies. We argue that under humanitarian law prolonged and blanket internet disruptions are similar to other kinds of disproportionate and impermissible forms of targeting or blockading of essential civilian infrastructure or services. The digital siege is constituted by varied forms and phases of network disruptions and shutdowns.

This report looks at these disruptions through the lens of international human right norms.

Livelihood consequences of the shutdown of August 2019 were severe, and losses suffered by various businesses during the first five months alone were estimated at Rs 178.78 billion, with more than 500,000 people having lost their jobs in the valley in the Kashmir Chambers of Commerce and Industry (KCCI) estimatesperiod.

Health indices showed a marked decline, with the months of June-August 2019 showing numbers of hospital visits dropping by upto 38%.

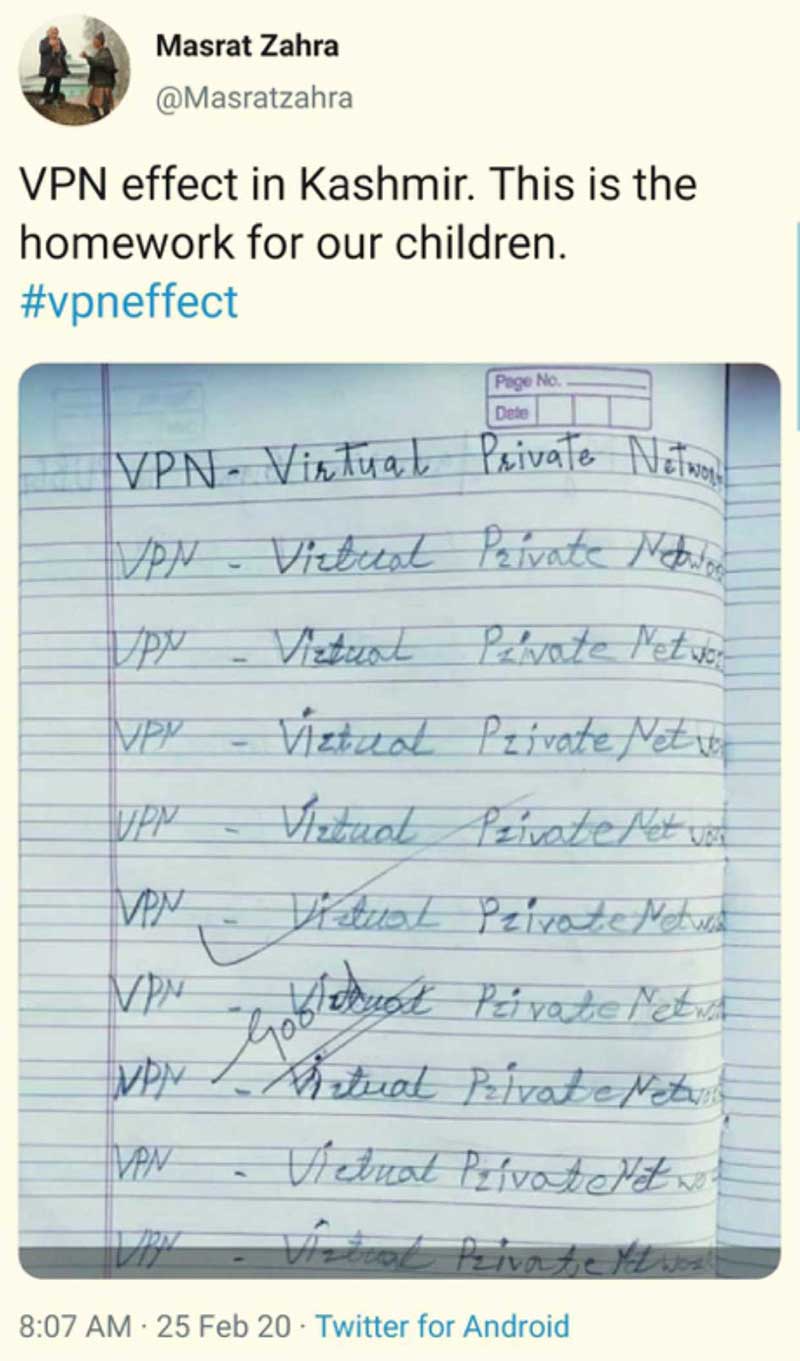

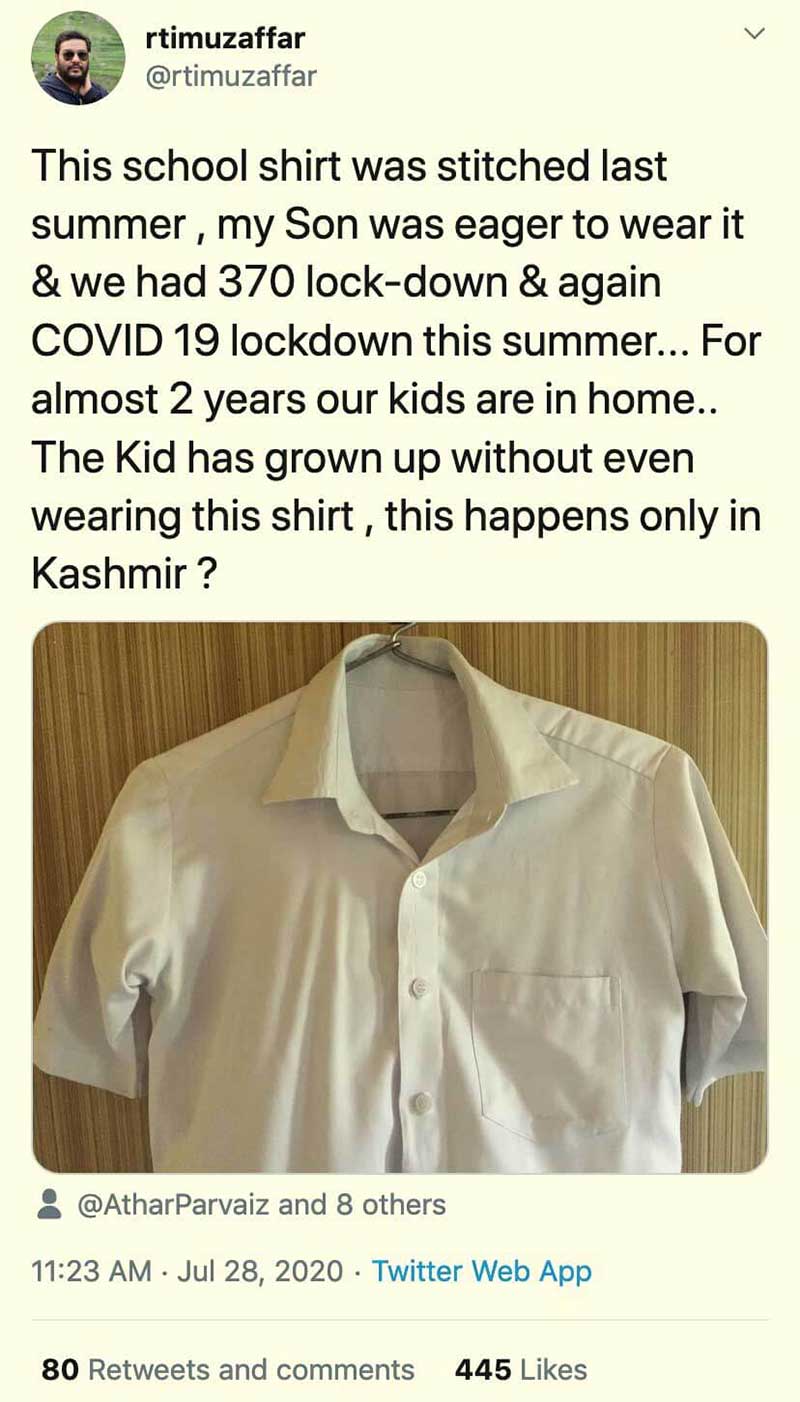

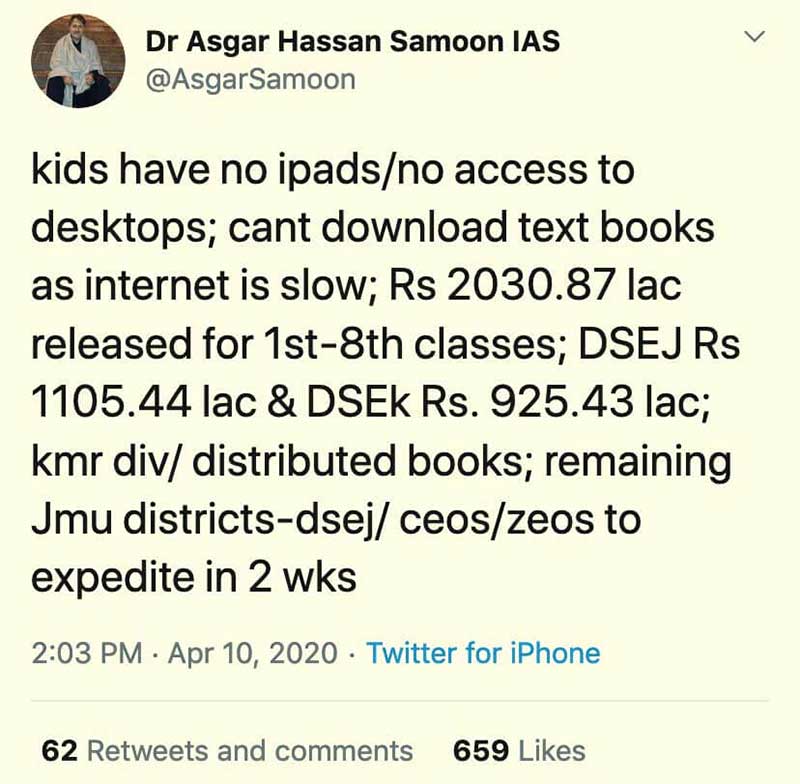

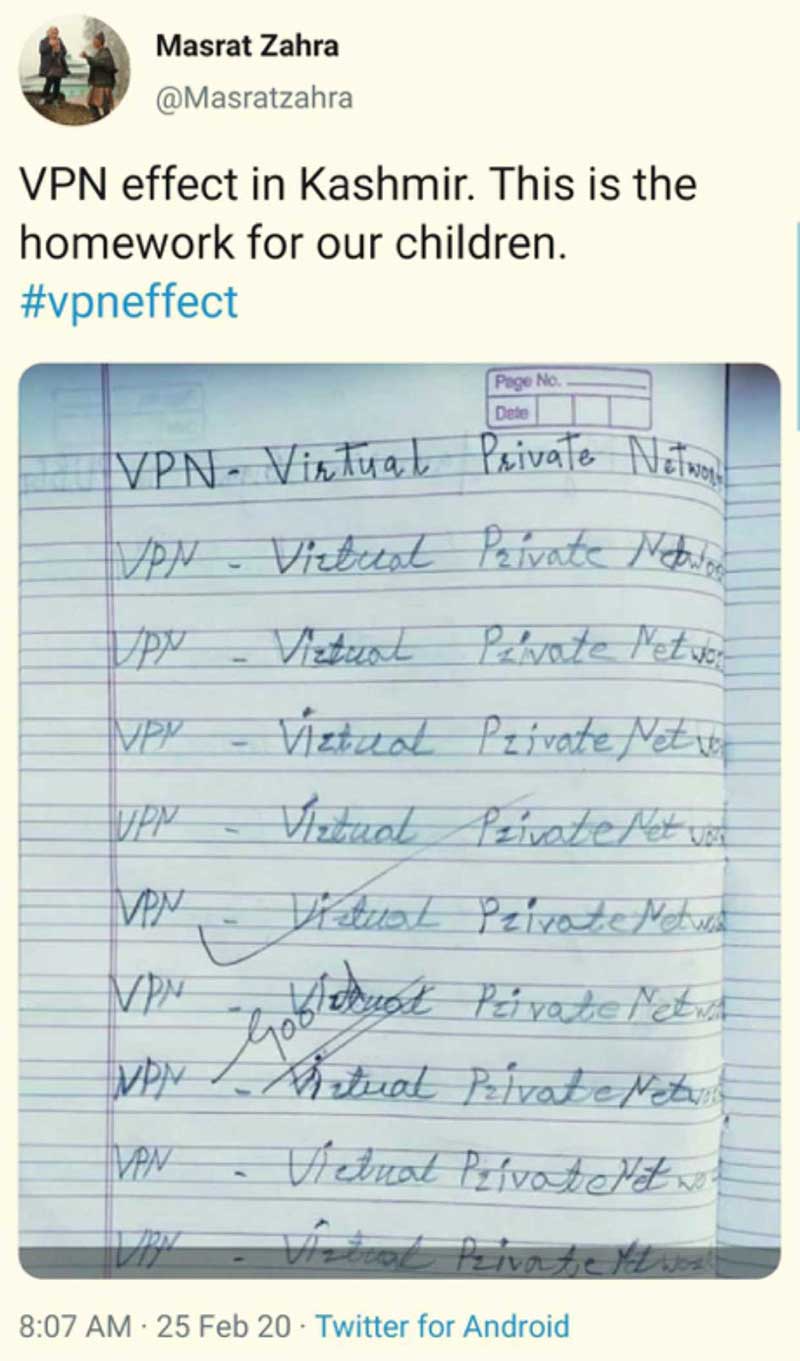

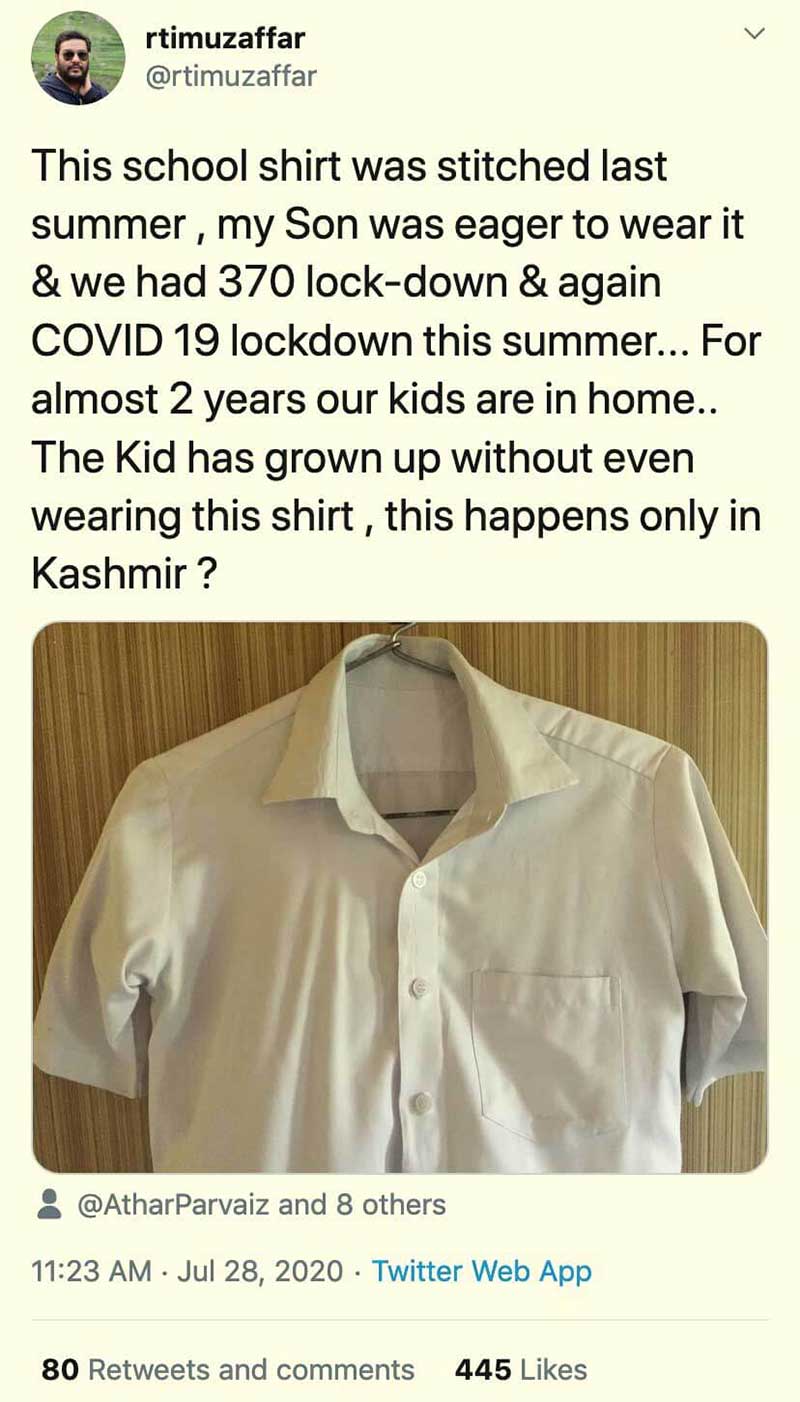

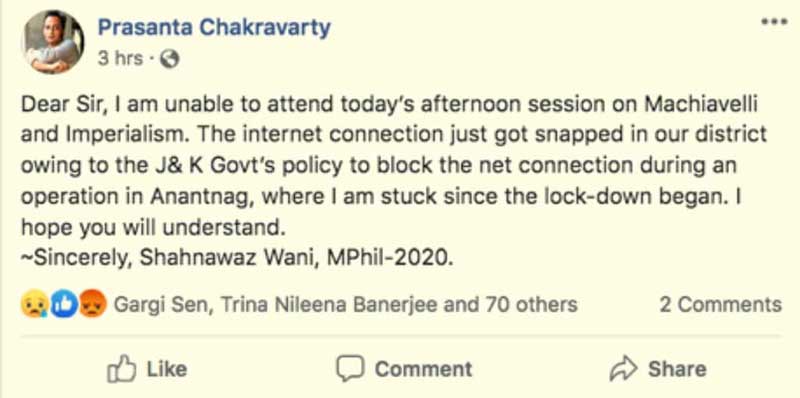

Education suffered a major setback, and in August 2020 students enrolled in Kashmir’s 30,000 schools and 400 institutes of higher education marked the first anniversary of the internet shutdown as a full year without attending school, or college or university.

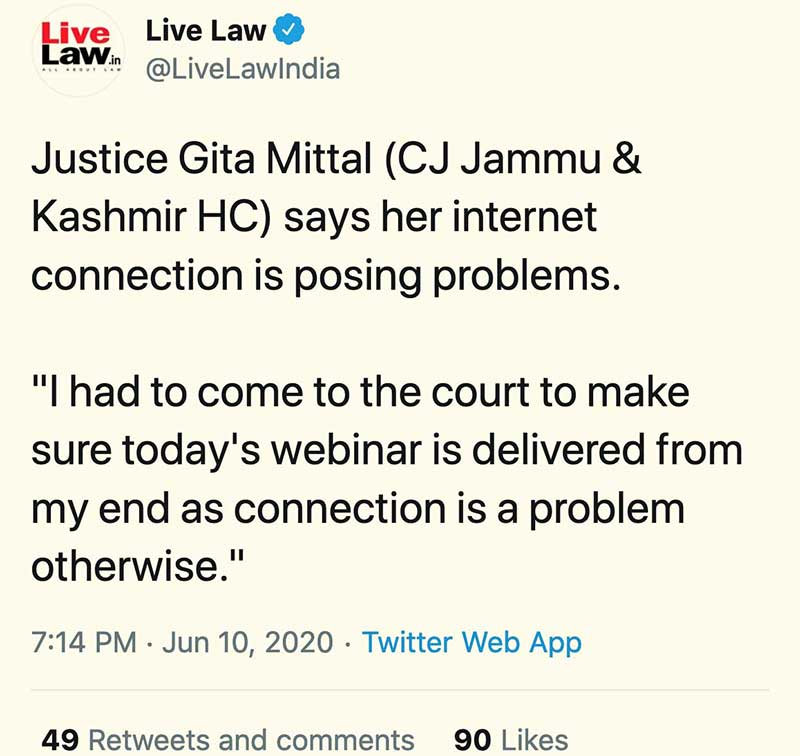

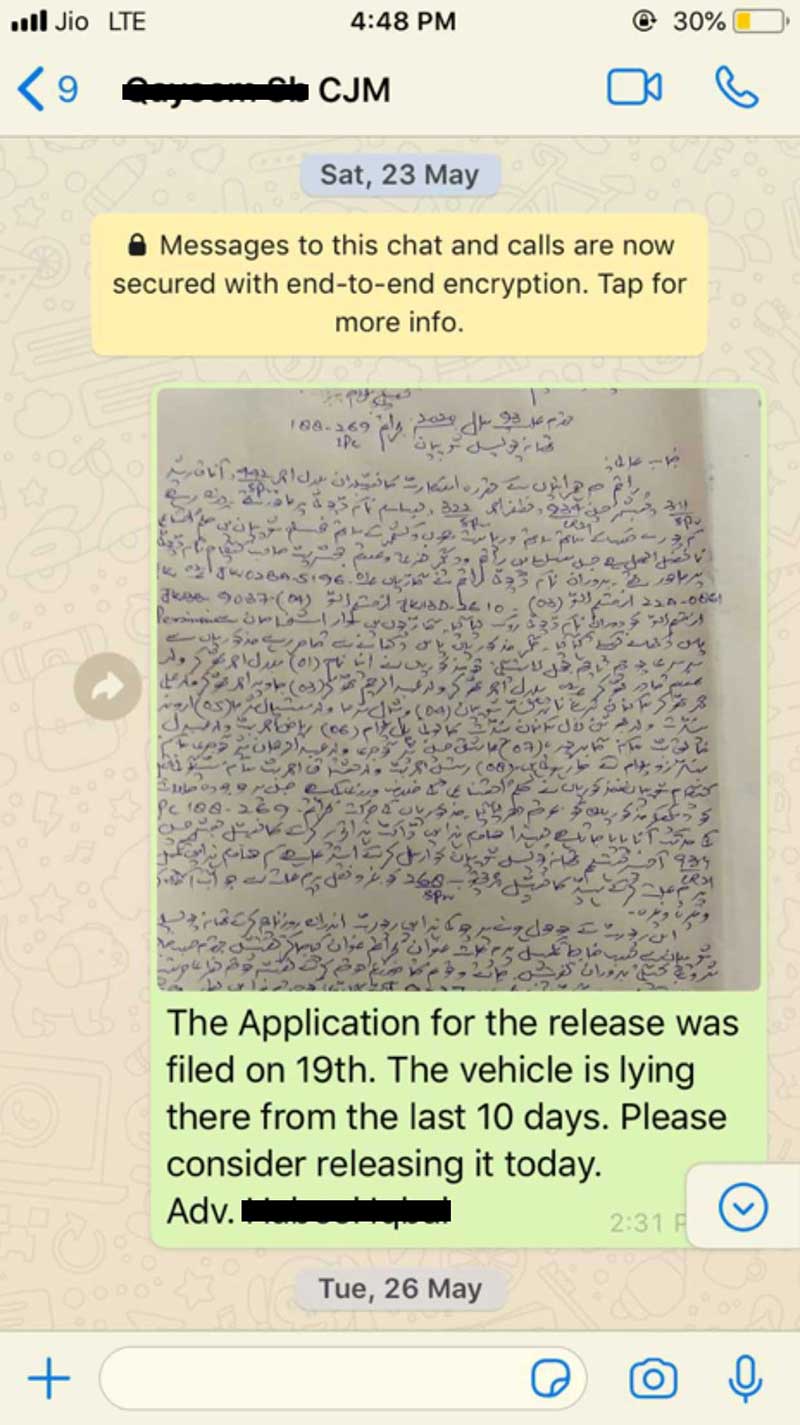

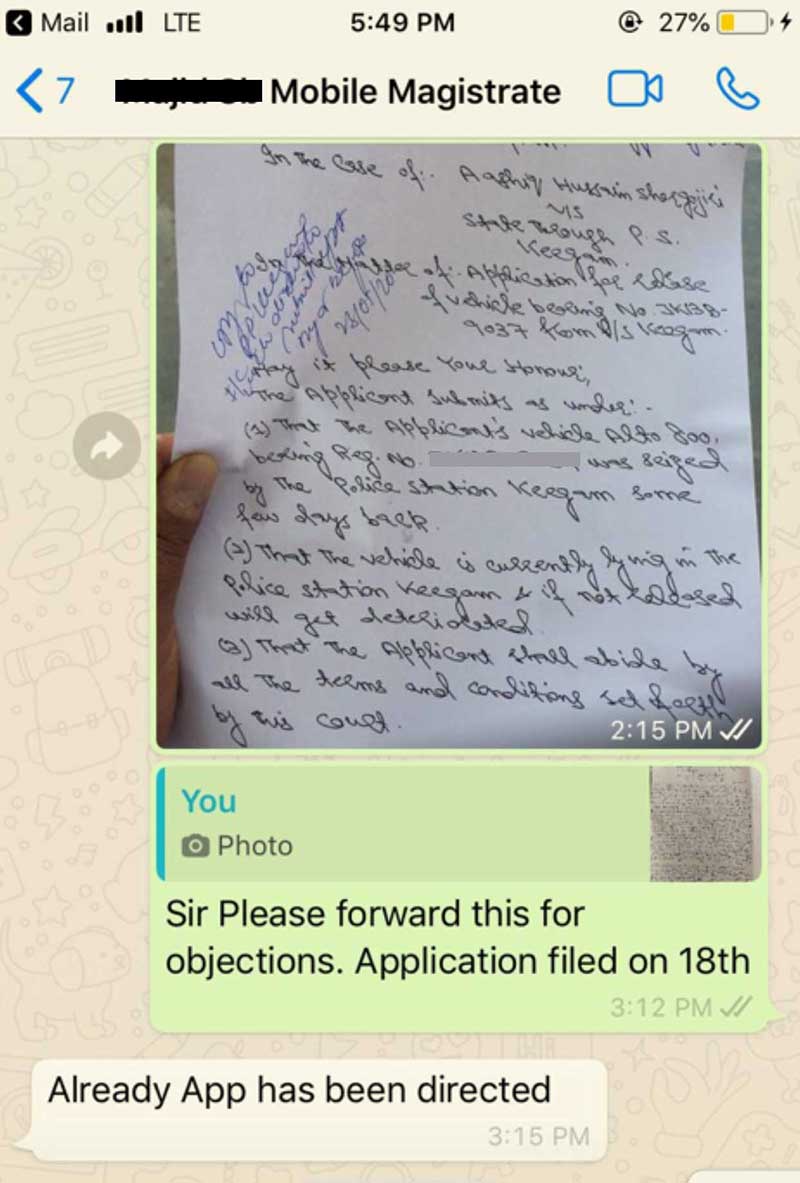

Justice saw systemic delays further compounded by ineffective online hearings. Amidst the internet and telecommunications blackout, more than 6000 detentions and over 600 ‘administrative’ detentions took place around August 5th 2019. Of habeas corpus petitions filed for the release of illegal detainees during the period, 99% remain Jammu & Kashmir Bar Association estimatespending .

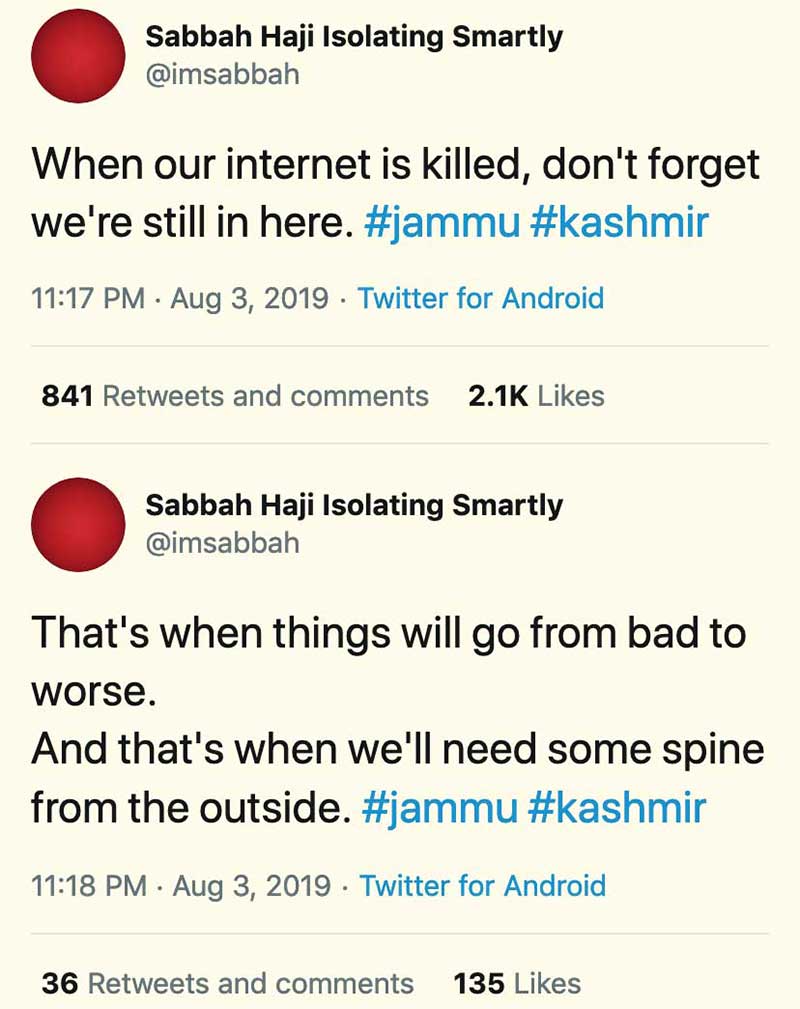

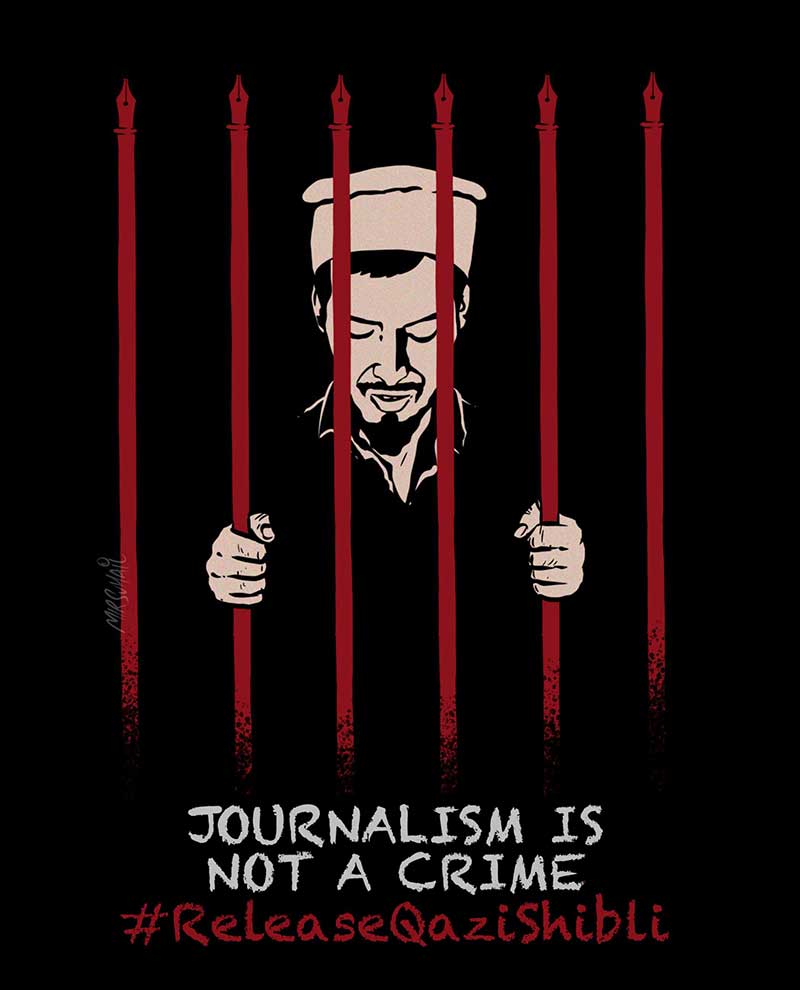

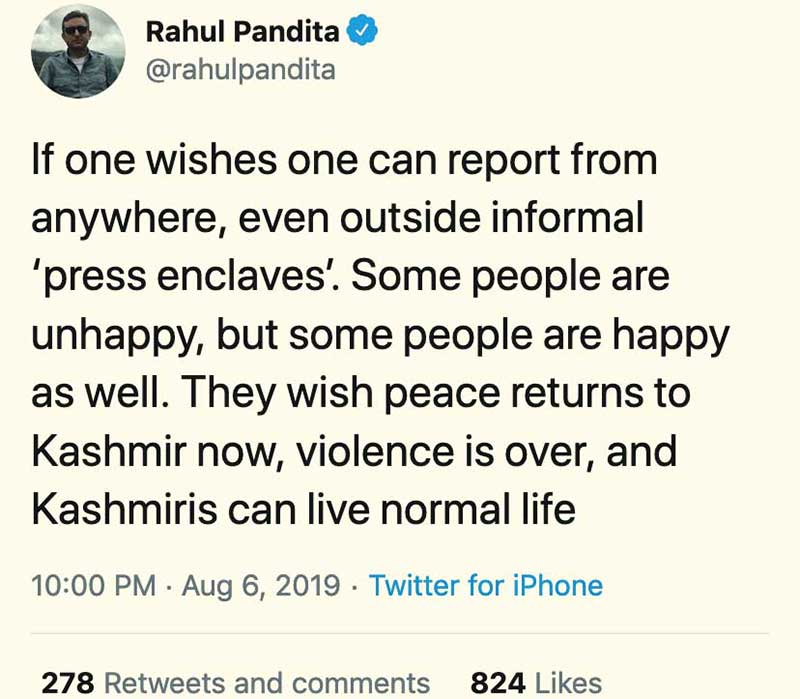

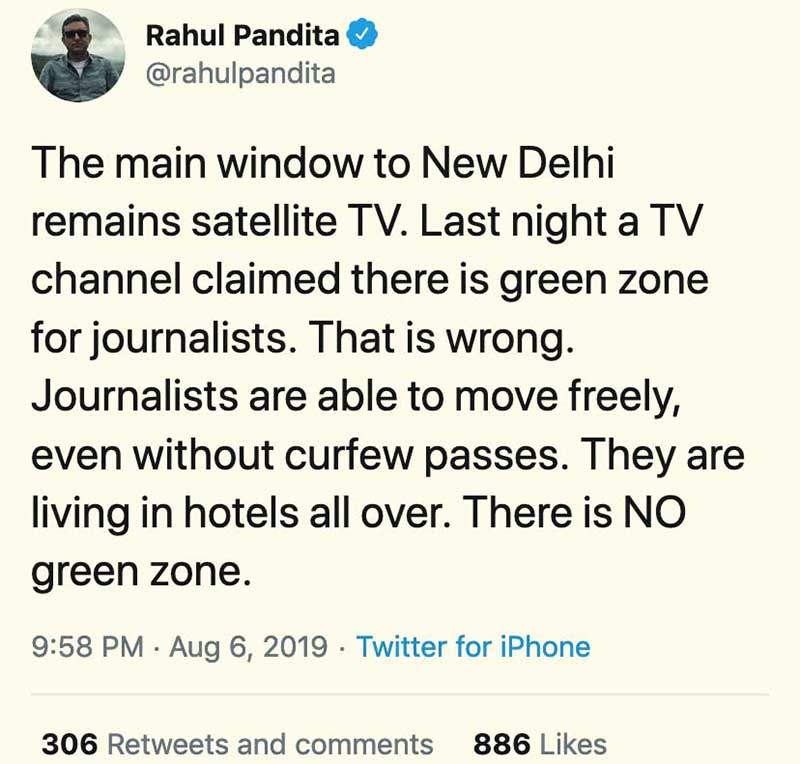

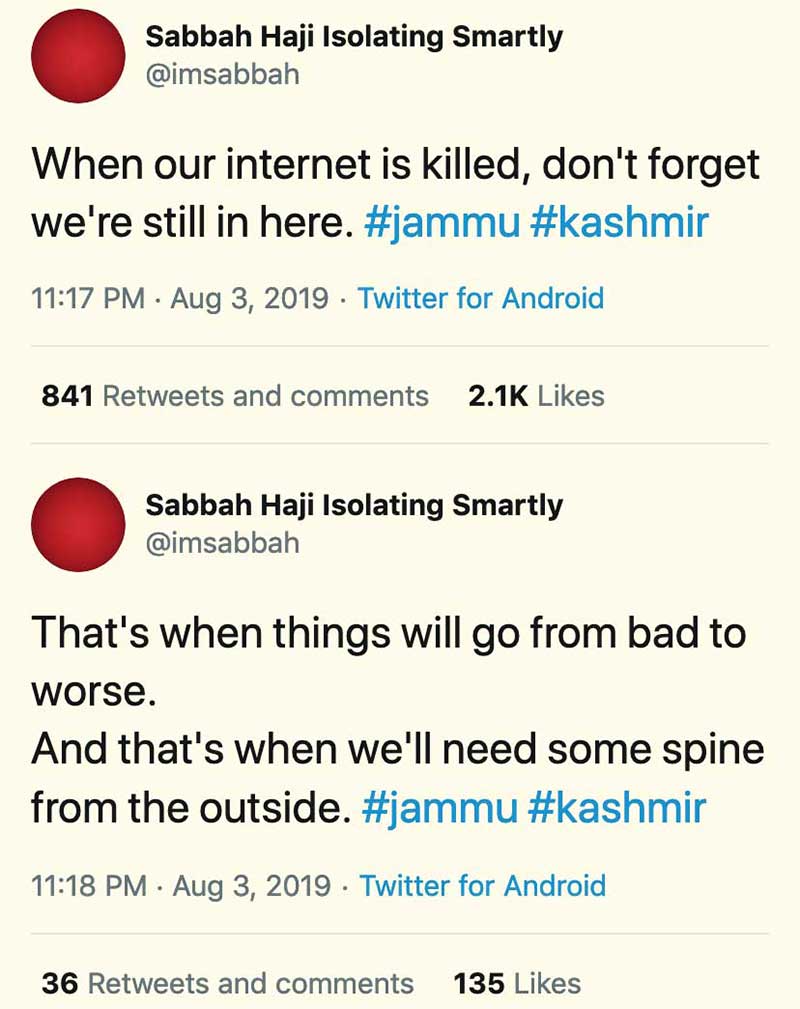

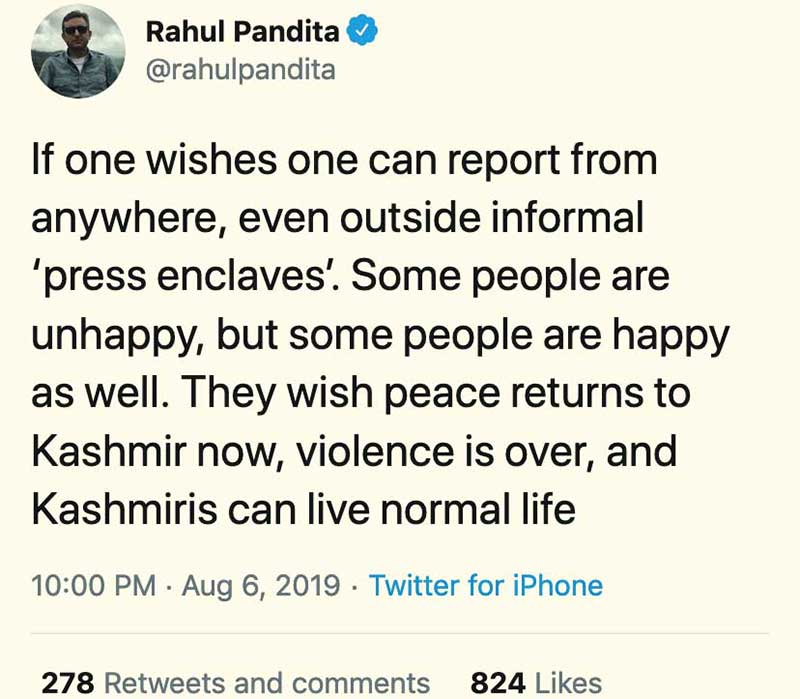

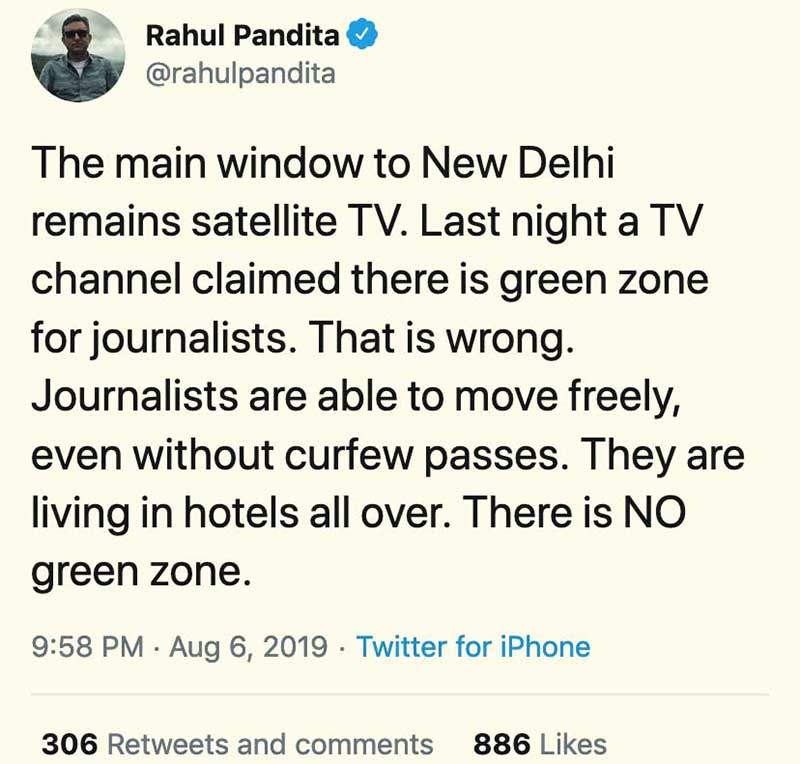

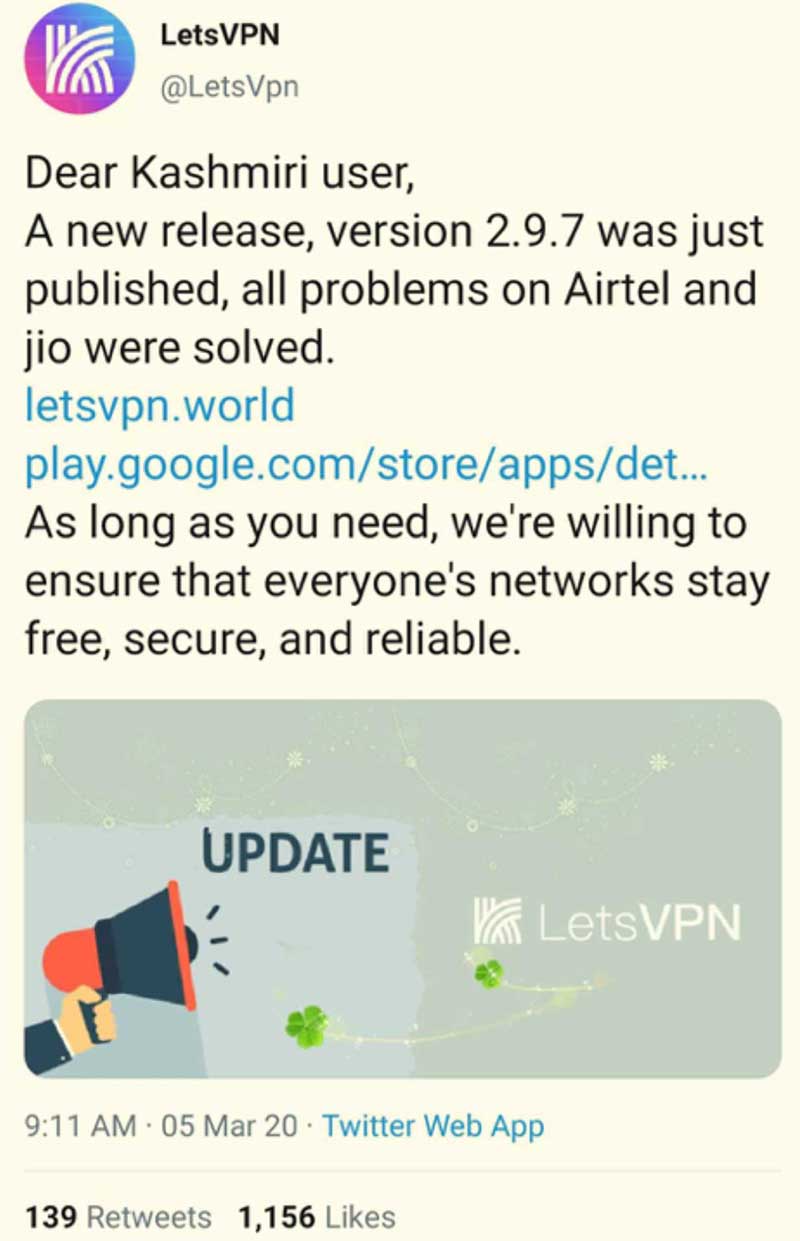

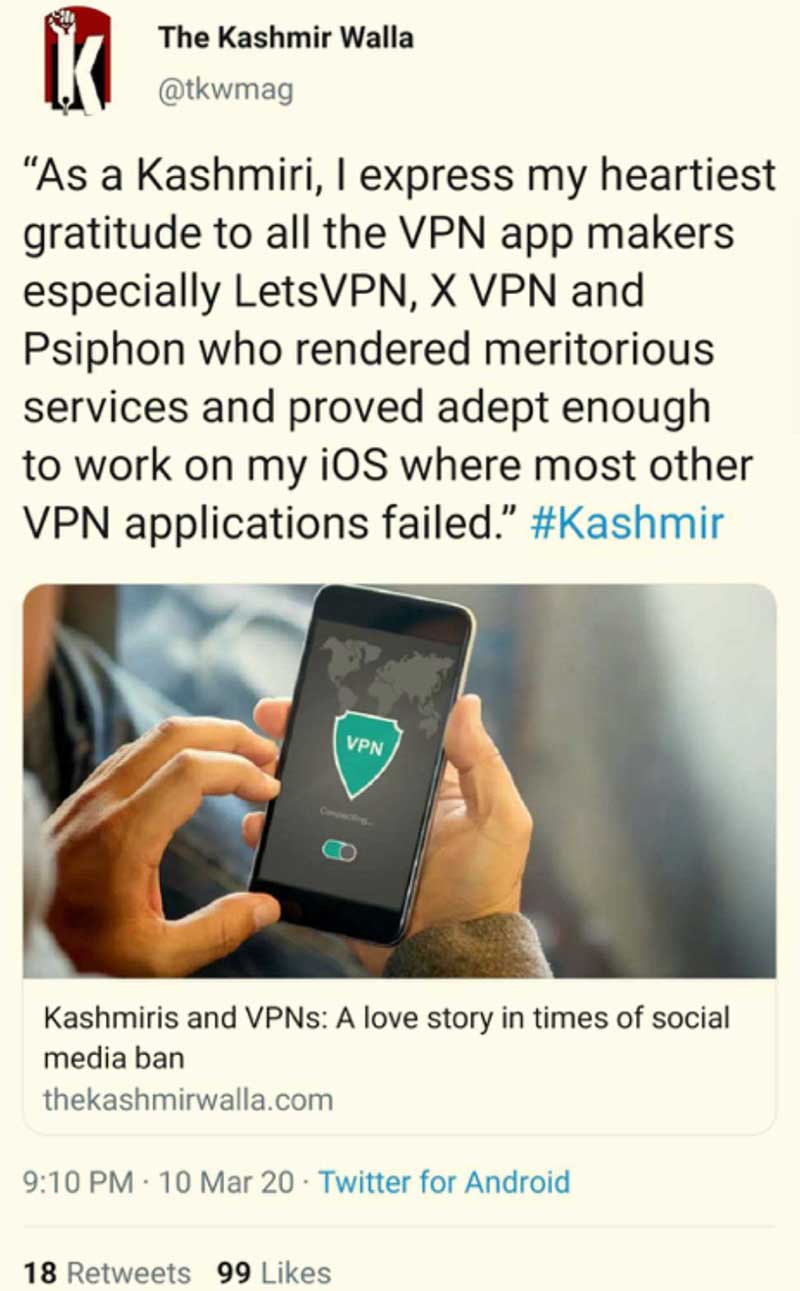

Press freedoms and the right to freedom of speech, expression and social participation suffered from the direct impact and chilling effects of online surveillance, profiling and criminal sanctions, with police complaints registered against working journalists and over 200 social media and VPN users.

This report unpacks the contexts of these disturbing facts, situating them in the light of fundamental human rights to livelihood, health, education, access to justice, freedom of press,free speech and expression, and social and cultural participation. The Covid-19 pandemic and the militarised lockdown in Kashmir re-instituted severe restrictions of mobility and public gatherings, compounding and complicating public health and other challenges of the network disruption. Despite widespread calls to restore full internet connectivity, and constitutional litigation before the Indian Supreme Court, the state continues to justify the throttling of internet speeds on grounds of national sovereignty, dismissing the concerns of international and Indian civil society actors.

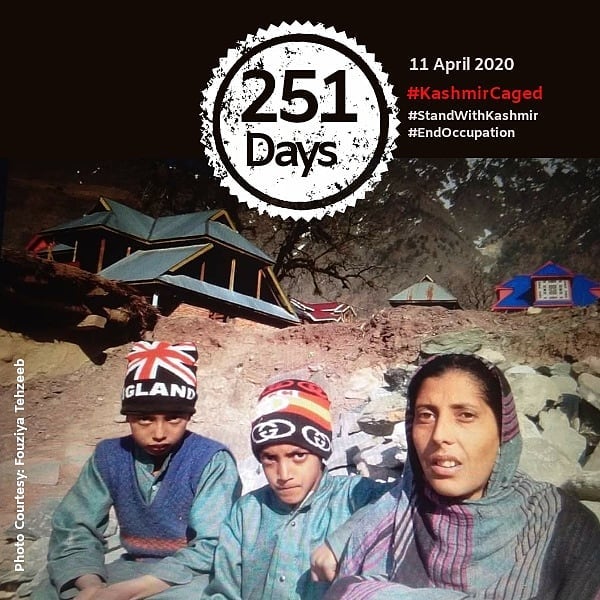

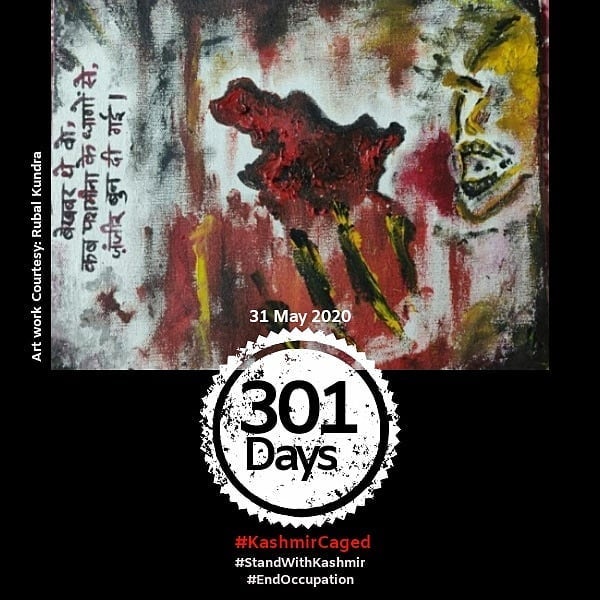

Through the chapters we focus on the layered impact of the pandemic and trace the consequences for differently located Kashmiris, including students, health workers, and journalists. Speaking with five individuals provides qualitative insights that animate and punctuate the narrative, and give us a glimpse into ordinary lives lived, and opportunities lost, amidst these crippling restrictions. Through a granular and detailed Timeline we present a temporal visualisation of the fluidity and complexity of the digital siege, as it unfolded through the first 300 days, across different regional geographies within Jammu & Kashmir.

Taken as a whole, Kashmir’s Internet Siege argues that the multi-faceted and targeted denial of digital rights is a systemic form of discrimination, digital repression and collective punishment of the region’s residents, particularly in light of India’s long history of political repression and atrocities. The promise of lasting peace, freedom and justice for the people of Jammu & Kashmir is inextricably tied to digital and human rights in the region.

background

As this report is being written, Jammu & Kashmir is under lockdown because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Yet, unlike the rest of the world, currently 12.5 million people in the region can barely video call their friends or family, attend online classes, webinars or conferences, use apps to have their groceries or medicines delivered, entertain themselves by streaming a film, or download the latest World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations and health guidelines. For the Internet in Kashmir has been restricted by the government, and mobile internet bandwidth is officially throttled to 2G levels (upto 250 kbps), a speed which does not allow full functionality for most web sites and web based applications. This present situation of highly restricted internet speeds is only the latest development in an on-going situation which saw a complete Access Now defines an Internet Shutdown as an "intentional disruption of internet or electronic communications, rendering them inaccessible or effectively unusable, for a specific population or within a location, often to exert control over the flow of information."internet shutdown as well as the blocking of all communications technologies (including voice calling on fixed line and mobile phones). These had been instituted as a "precautionary" security measure in the run-up to the political changes that were initiated in Jammu & Kashmir on August 5th 2019.

This report provides an overview of the harms, costs and consequences of the digital siege in Jammu & Kashmir, from August 2019 to the publication of this report in August 2020. We examine the disruption of network connectivity through a broad-based and multi-dimensional human rights framework that sees internet access as vital to life in the contemporary world. The Internet and social media play an essential role in democratizing the public sphere, facilitating social and economic engagement, mobility and communications, removing barriers to knowledge and information, all while creating an important avenue for solidarity and organizing.

This report moves beyond the most often cited direct impact of network disruptions on political and economic freedoms of speech and association, business and trade. We include studies of the effect on the rights to health, education, and livelihood and examine the effects of network disruptions on access to justice and individual and collective security. We also consider the damage done to social and cultural life, which is the basis of the economy and community. In doing so we hope Kashmir’s Internet Siege provides a more integrated, cross-sectoral, and wide ranging view of the devastating and all-encompassing impact of the government’s denial of communications and access to the internet (and the throttling of internet speeds once access is restored). Individual chapters that contextualise the situation in Kashmir in the light of particular human rights standards, and a detailed timeline, are interwoven with brief conversations that highlight the intersecting nature of the discrimination and suffering caused. The report distills the voices and experiences of the siege from a multiplicity of media accounts and published sources, as an all India Covid 19 lockdown placed severe constraints on our ability to undertake field visits, carry out primary research, and conduct face-to-face interviews.

context of the siege

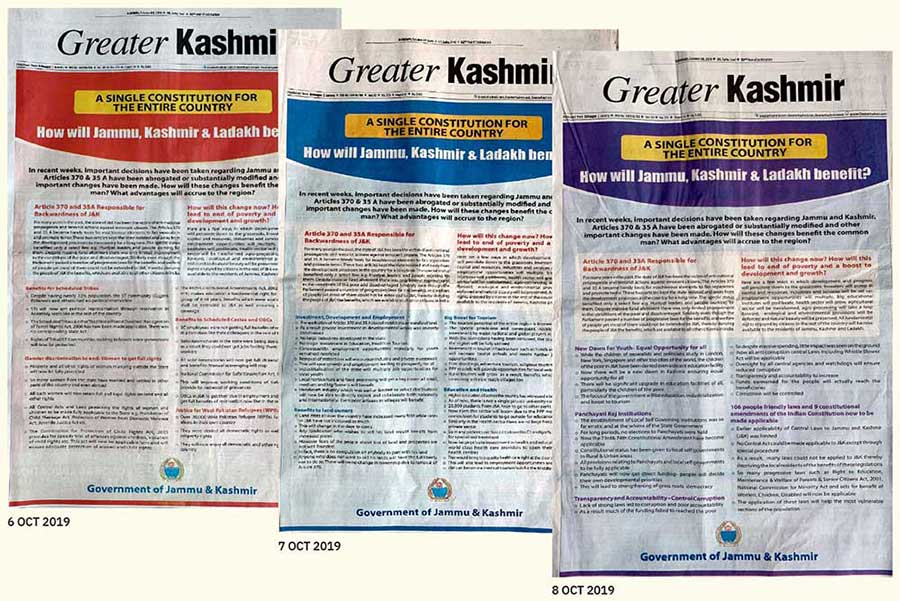

On August 5th 2019, Indian parliament amended Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, which, based on the Instrument of Accession signed by the Maharaja of Jammu & Kashmir,was formulated to enable Jammu & Kashmir a semi-autonomous ‘special status’ and its own Constitution. The Indian parliament also approved the partition of the State of Jammu & Kashmir into two directly administered Union Territories - Jammu & Kashmir, and Ladakh. While rumours had been circulating during the week previous to this momentous decision about the impending imposition of security restrictions, and the possible detention of high profile Kashmiri politicians, no one was prepared for the siege that followed. Through the last year, amidst restrictions on the internet that make it difficult to access information—including government notifications—the people of Jammu & Kashmir have been subject to further far reaching and undemocratic changes to laws relating to land and property ownership, governance and permanent residency rights. These legal changes have destroyed every remaining trace of Kashmir’s constitutional autonomy or resource sovereignty, both de jure and de facto.

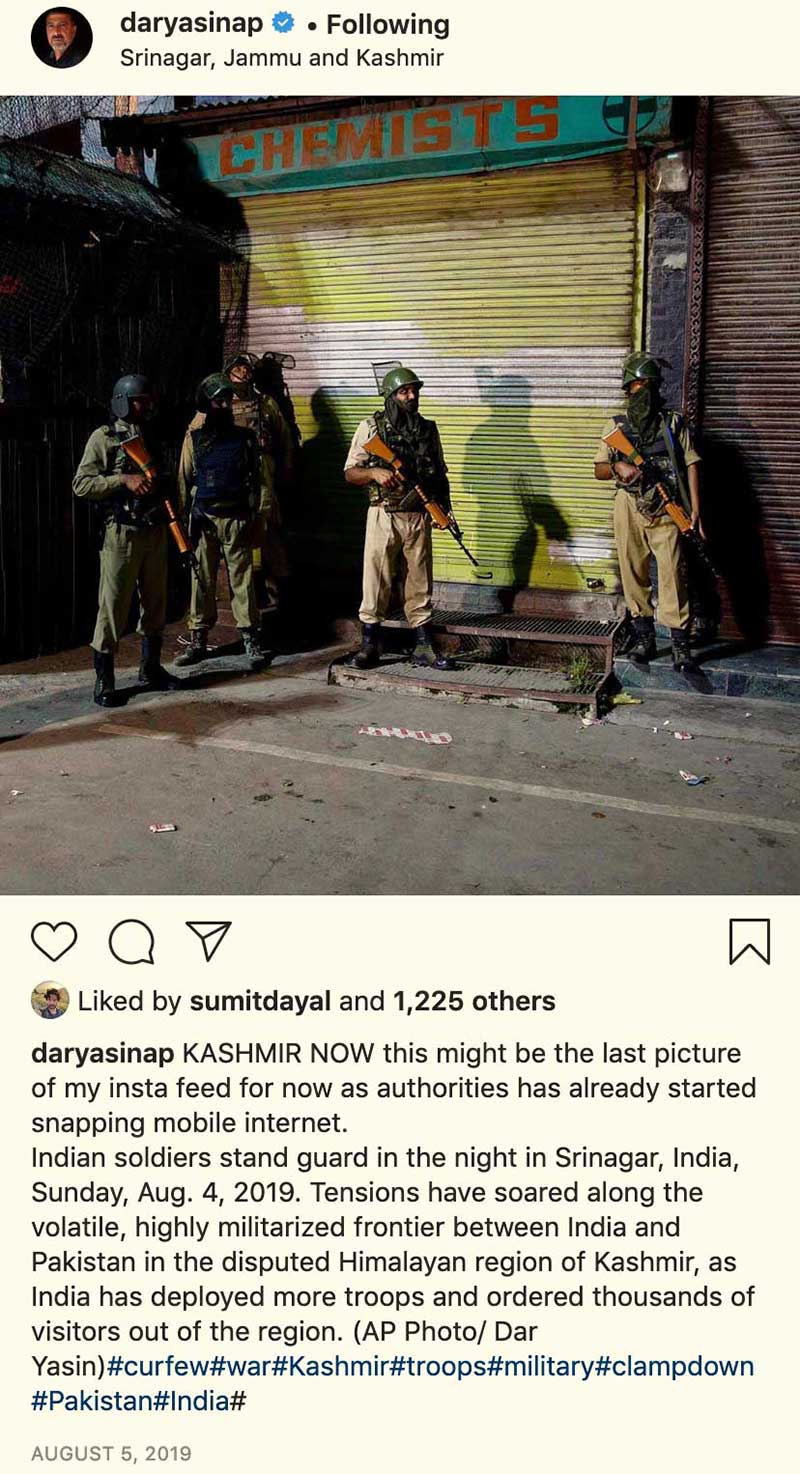

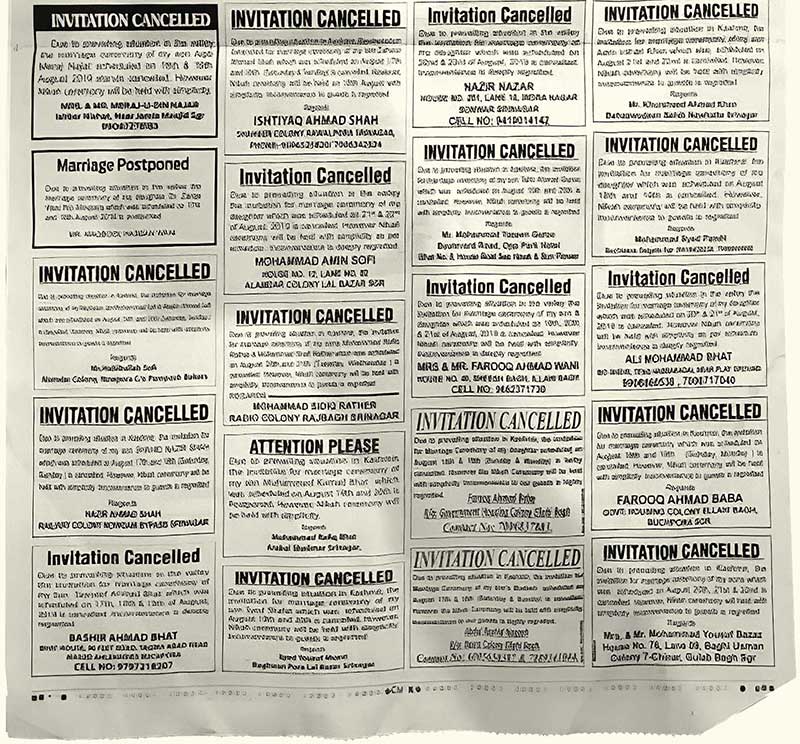

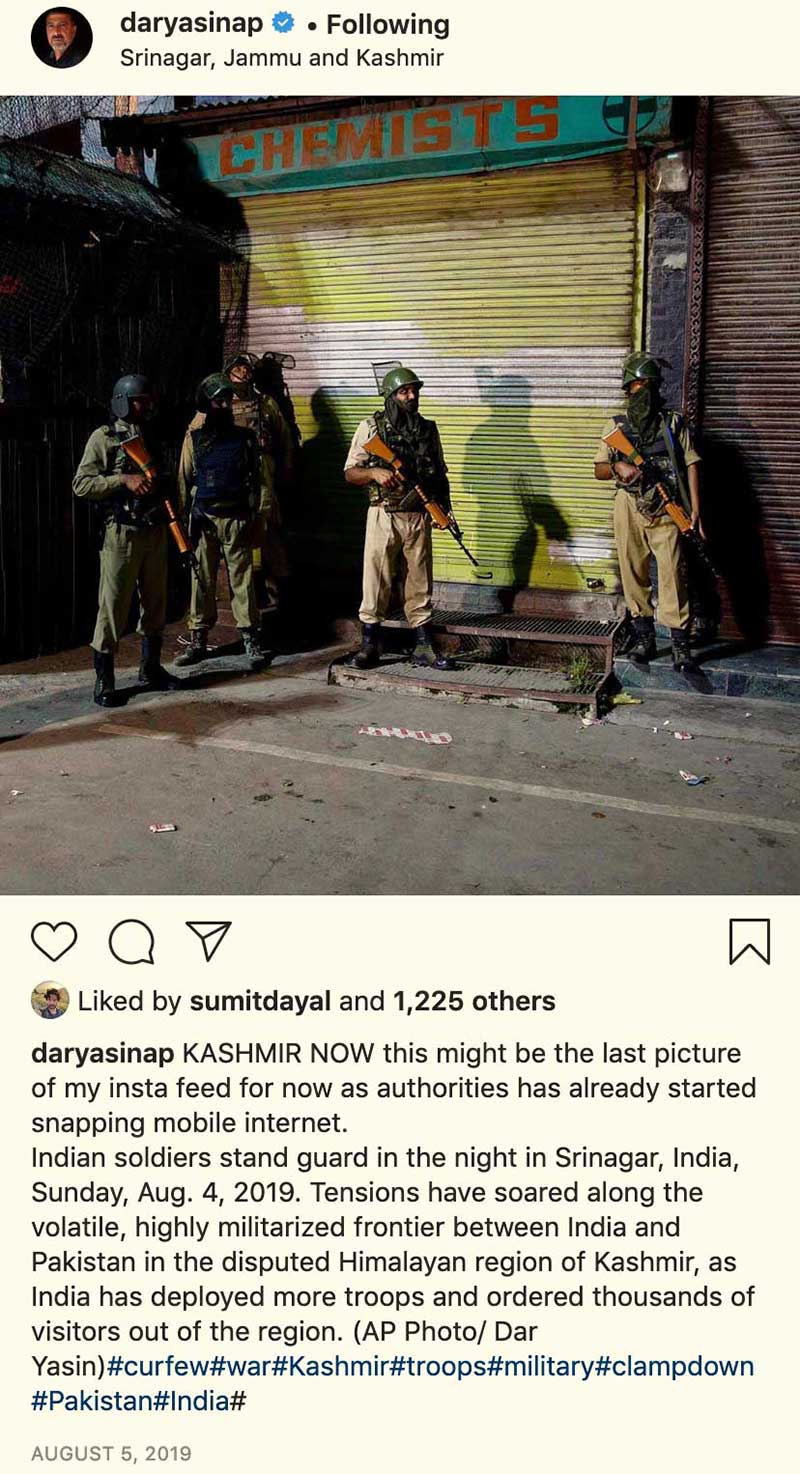

Kashmiris are long accustomed to such ‘sieges’, which feature highly intrusive security measures that include blockading of arterial roads and entry and exits to the Kashmir valley, curfew-like restrictions on mobility, mass preventive detentions, and telecommunication and internet blackouts. However this time around the intensity of measures underway, including large scale troop movements, the mass evacuationsof tourists, of non-Kashmiri students, and of Hindu pilgrims on the Amarnath Yatra pilgrimage, all ostensibly due to a "terrorist" threat, created widespread and unprecedented panic. Finally around 9 pm on August 4th 2019, the government suspended all phone lines as well as the Internet. Although the phone lines were gradually restored a month later, followed by broadband internet and the mobile internet, even a year later internet data speed continues to remain throttled on mobile connections throughout Jammu & Kashmir.

According to statistics published by the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI, 2019) undivided Jammu & Kashmir had a total of 11.44 million telecommunications subscribers (both phones and internet) and 6.60 million internet subscribers (more than double of 3.65 million subscribers in 2014.) Broadband internet subscribers numbered 5.90 million (up from only 0.53 million in 2014) while wireless internet subscription (referred to as mobile internet) was at 6.49 million. Unsurprisingly, the internet shutdown of August 2019 had an enormous impact on digital access and teledensity in the region. New Indian Express reported that "wireless subscription data released by TRAI shows that the region also recorded a sharp dive in its overall mobile subscriber base during August and September [2019], shedding a net 2.58 lakh [258,000] users." The contraction in mobile user base in the same period saw the region record a net decline of 115,000 wireless subscribers during the period, compared to a net addition of 144,000 mobile connections during the previous quarter ended June 30, 2019. A loss of 1.4 million telecom subscribers and a negative growth of 12.59% of Kashmir’s telecom sector were recorded in the first quarter of 2020, the Andalou Agency reported.

a history of blockades

Indian Administered Kashmir, like the other parts of the erstwhile kingdom of Jammu & Kashmir, has been disputed territory ever since the independence of Pakistan and India in Indian Administered Kashmir, comprises the southern and southeastern portions of the former princely state of Jammu & Kashmir. It comprises three administrative divisions Jammu, Kashmir and Ladakh, which previously constituted the Indian state of Jammu & Kashmir. Since August 5th 2019 it has been partitioned into two directly ruled Union Territories of "Jammu & Kashmir" and "Ladakh". The northern and western portions of the disputed region are administered by Pakistan and comprise three areas: "Azad Kashmir", Gilgit, and Baltistan. In this report we use "Jammu & Kashmir" to refer to Indian Administered Kashmir, and "Kashmiris" to refer to residents of this territory1947. It has been home to a longstanding movement for self-determination, and for thirty years, witness to an armed rebellion. The government’s response has been heavy-handed and destructive; amongst other systemic and widespread patterns of human rights violations, documented in landmark reports by the United Nations in 2018 and 2019, Kashmir has witnessed the ubiquitous use of internet and telecommunications disruptions. Such prolonged and crippling digital sieges are a technique of political repression and a severe impediment to the enjoyment of constitutionally and internationally guaranteed civil, political and socio-economic rights. They curtail circulation of news and information, restrict social and emergency communications, and silence and criminalise political interactions and mobilisations.

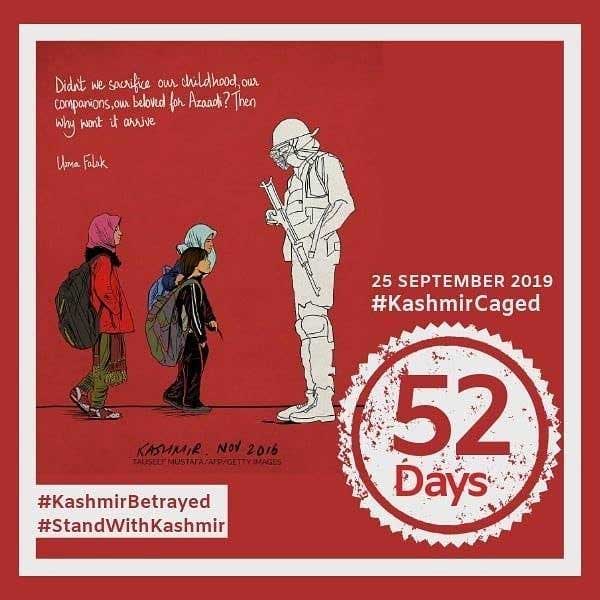

India leads the world in ordering internet shutdowns, and both in terms of frequency and duration Jammu & Kashmir accounts for more than two-thirds of Indian shutdowns. There have been 226 documented internet shutdowns in Jammu & Kashmir since the year 2012. Currently, even the 2G internet access available to Kashmiris remains extremely precarious as localized shutdowns of the internet, often accompanied by mobile phone disruptions, remain commonplace, sometimes lasting for a week. As this report goes to press, there have been 70 separate shutdowns in 2020. Technology researcher, Prateek Waghre estimates a loss of around 3.5 billion hours (and counting) of disrupted internet access for approximately 12.25 million people. After 213 days (before 2G internet was partially restored in March 2020), the internet shutdown that began on August 4th 2019, was described as the longest running Internet shutdown in a democracy, and the second longest in the world, after Myanmar.

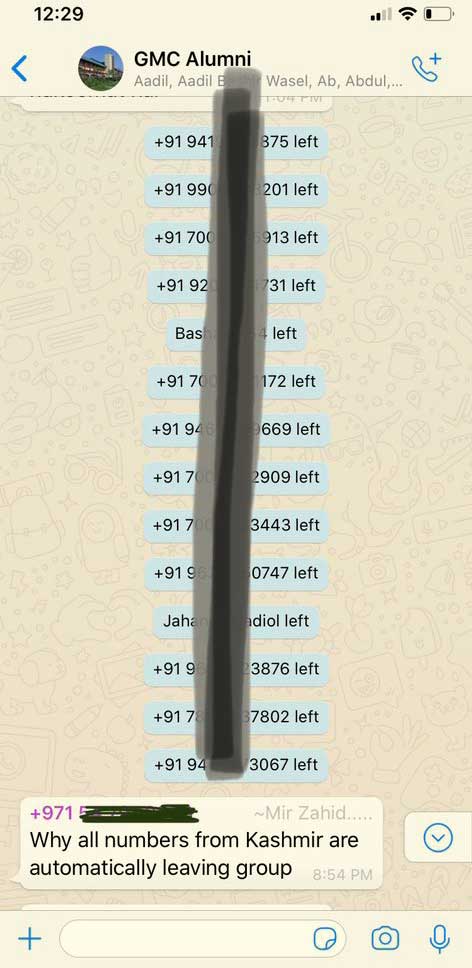

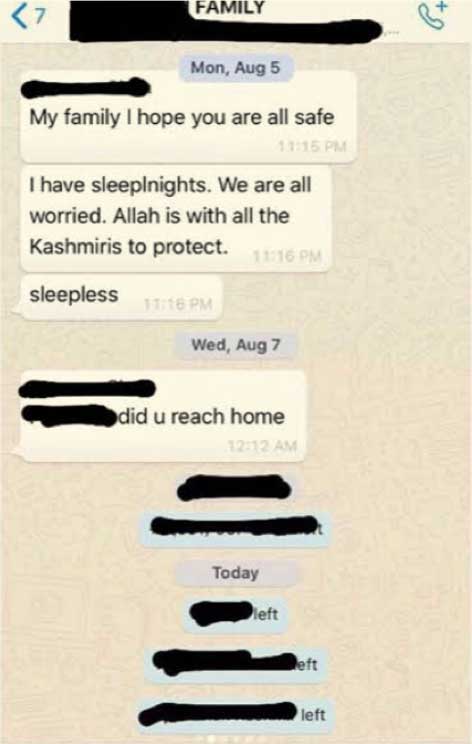

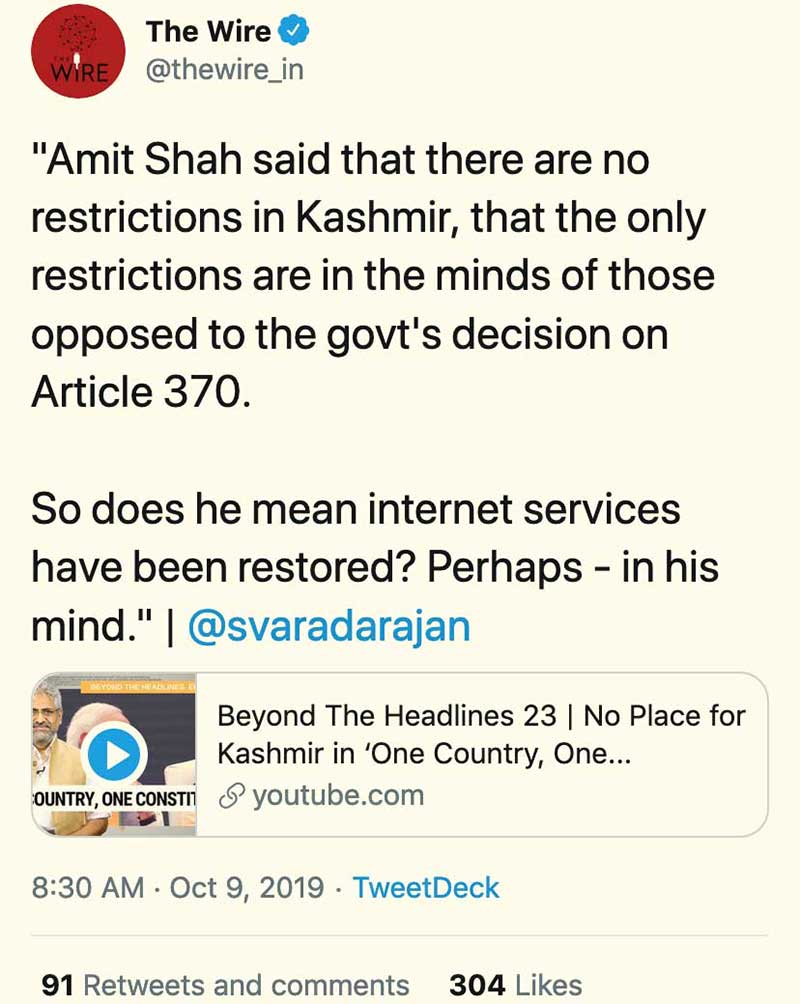

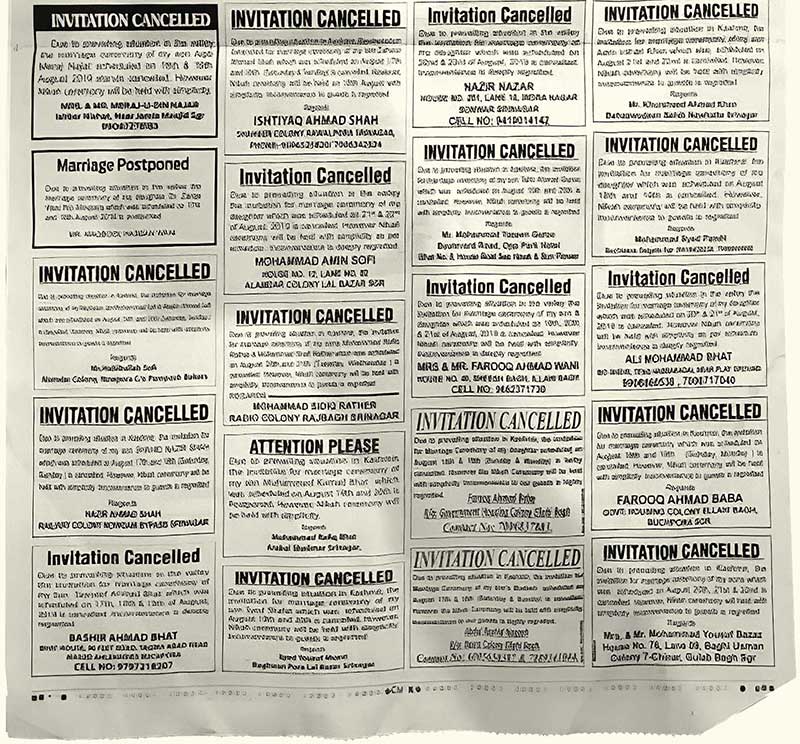

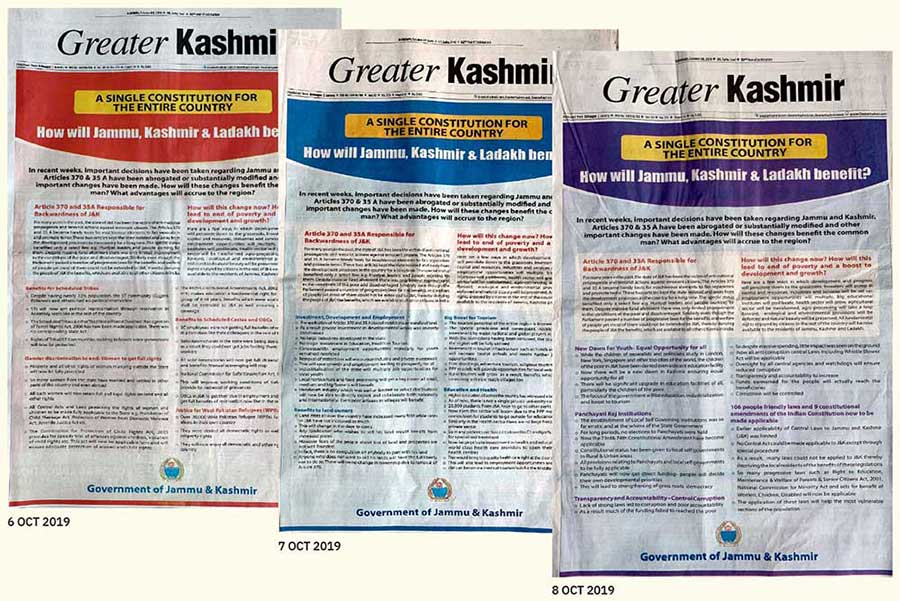

The news of the August 5th abrogation of Article 370 and Article 35 A, of vital concern for the political future and rights of Kashmiris, was not available to most due to the overnight shut-down of phones, the internet, as well as cable television channels; though the rest of the world could watch it unfold in real time in the Indian Parliament. In subsequent weeks, it became clear that the internet blackout was one of a slew of repressive and violent measures adopted by India to crackdown on political mobilisations and protests in Kashmir, and to prevent news from Kashmir reaching the world. This was in keeping with long standing practices of using coercive and disproportionate force (such as bans on organisations, prohibitions on public gatherings, preventive detention, and criminal and extra judicial sanctions), against all forms of political expression and legitimate dissent in Kashmir, by equating political expression and activism, with threats to national security, "militancy" and "cross border terrorism." Widespread human rights violations were reported in this period, including custodial torture, use of excessive force, enforced disappearances, and thousands of arbitrary detentions including those of children. Large scale societal distress and chao, including loss of lives, ensued, as people could not access health and emergency services, or get in touch with missing loved ones. All of this unfolded in the midst of undeclared martial law, mass detentions with people held incommunicado, military barricading and restrictions on mobility, and an overarching atmosphere of terrifying uncertainty.

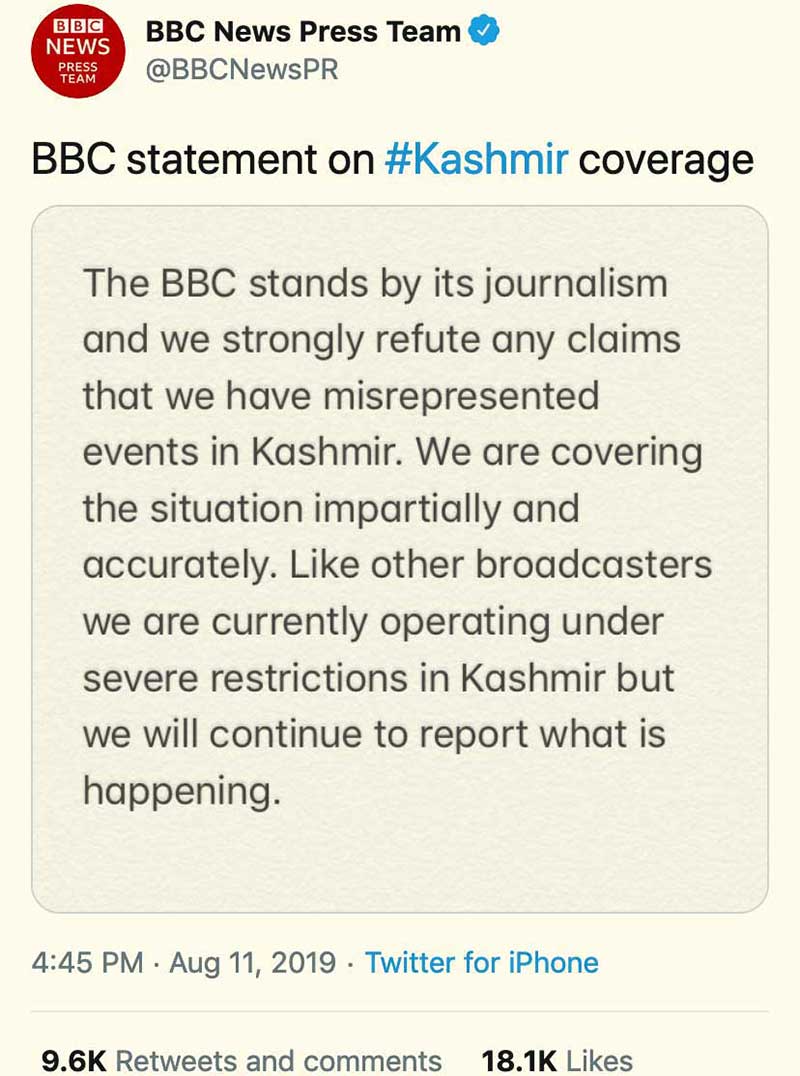

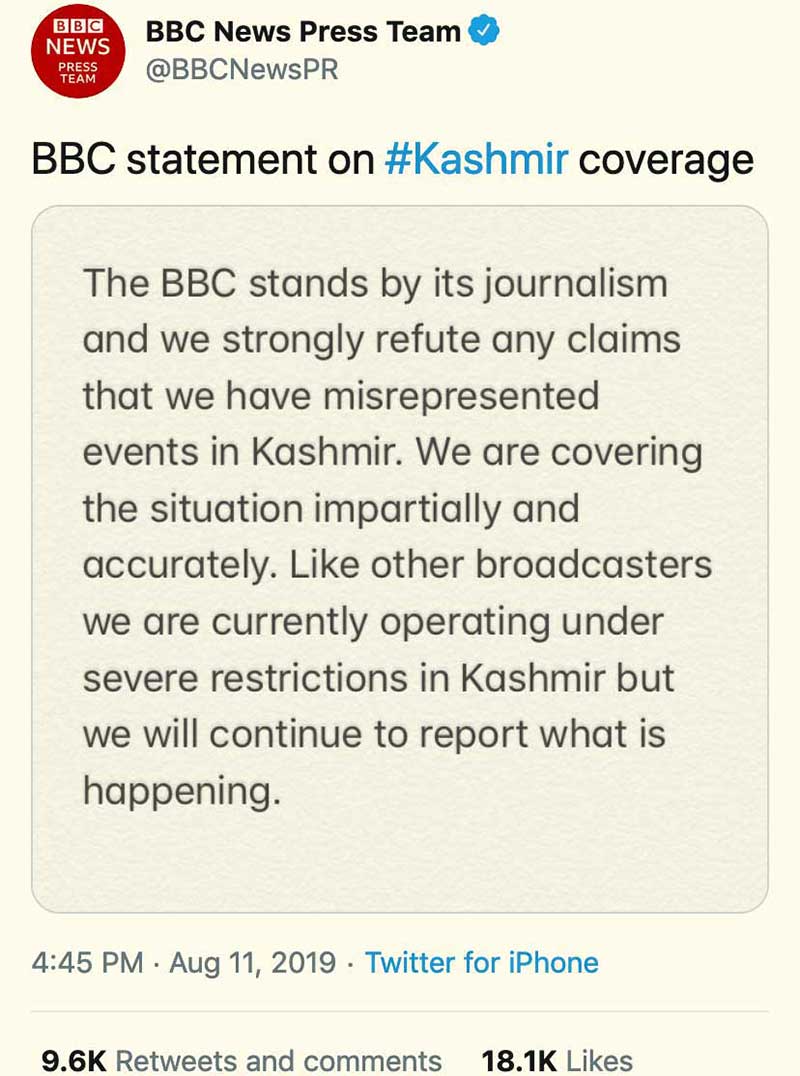

The extraordinary efforts and courage of local journalists, and Indian and international news organisations, ensured that news of the escalating humanitarian and human rights crisis began to trickle out despite the communications blackout. Instead, the unprecedented shut down itself became an international news story. In a letter addressed to the Indian government asking for a restoration of the Internet, a group of five UN Human Rights Experts, including the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Speech and Expression, David Kaye said, 21 "The shutdown of the internet and telecommunication networks, without justification from the Government, are inconsistent with the fundamental norms of necessity and proportionality [...] The blackout is a form of collective punishment of the people of Jammu & Kashmir, without even a pretext of a precipitating offence."

internet governance in a militarised state

Prior to the Constitutional amendments of August 5th 2019, Indian laws and the jurisdiction of regulatory bodies were largely extended to Jammu & Kashmir through notification, or through the enactment of state specific laws (such as the Ranbir Penal Code which dealt with offenses analogous to the Indian criminal laws.) Since the abrogation and consequent legal changes, 106 Indian laws, including the Indian Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 now apply directly to Kashmir, along with those Jammu & Kashmir legislations that have been retained or amended.

The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) and the Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal are independent regulatory and adjudicatory bodies for the telecommunication sector, empowered to adjudicate disputes, and protect the interests of service providers and consumers of the telecom sector. Their jurisdiction extends to Jammu & Kashmir by virtue of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India Act, 1997. TRAI ordinarily adopts a consultative process on important issues related to the telecommunication and broadcasting sectors and periodically issues statements and reports on the state of the sector. For instance, it recently issued a directive asking telecom companies to extend the validity of pre-paid SIM cards during the recent nationwide Covid-19 lockdown, to ensure that subscribers get uninterrupted services. In contrast, it has maintained a studied silence on the impact of government policies of severe telecommunications restrictions on stakeholders in Kashmir, including consumers and service providers in the region.

India justifies internet restrictions in Jammu & Kashmir on grounds of national security, public order, and the need to prevent the spread of disinformation, citing the armed conflict and counter- terrorism operations against Pakistan. In practice, internet shutdowns in Kashmir have emerged as a routine law enforcement mechanism instead of an extraordinary measure, imposed both as a reaction to and precaution against a variety of actual and perceived "threats" and events that range from street protests, police action, militant attacks and military operations, to elections, visits by official or diplomatic delegations, public funerals, strikes and even the viral circulation of videos depicting atrocities. The frequency with which restrictions are imposed as a ‘precautionary measure’, for instance on Indian national holidays like Republic Day and Independence Day, or during religious festivals like Muharram, make clear the routine nature of their deployment.

Digital rights violations in Kashmir also cover a broad plethora of instances, ranging from complete telecommunication blackouts to the throttling of speed, partial and localised shutdowns or content blocking affecting certain kinds of access or users, ‘white-listing’ and ‘black-listing’ of websites, ‘shadow bans’, and the unauthorised use of surveillance and jamming technologies. The legal basis and grounds for imposing such restrictions are rarely made public, although the recent judgments in Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India and Foundation for Media Professionals v. Union Territory of Jammu & Kashmir have somewhat ameliorated this position in the law. The climate of deniability and lack of accountability for violations is compounded by the multiplicity of legislation, broad discretionary executive powers, and the lack of effective judicial redress.

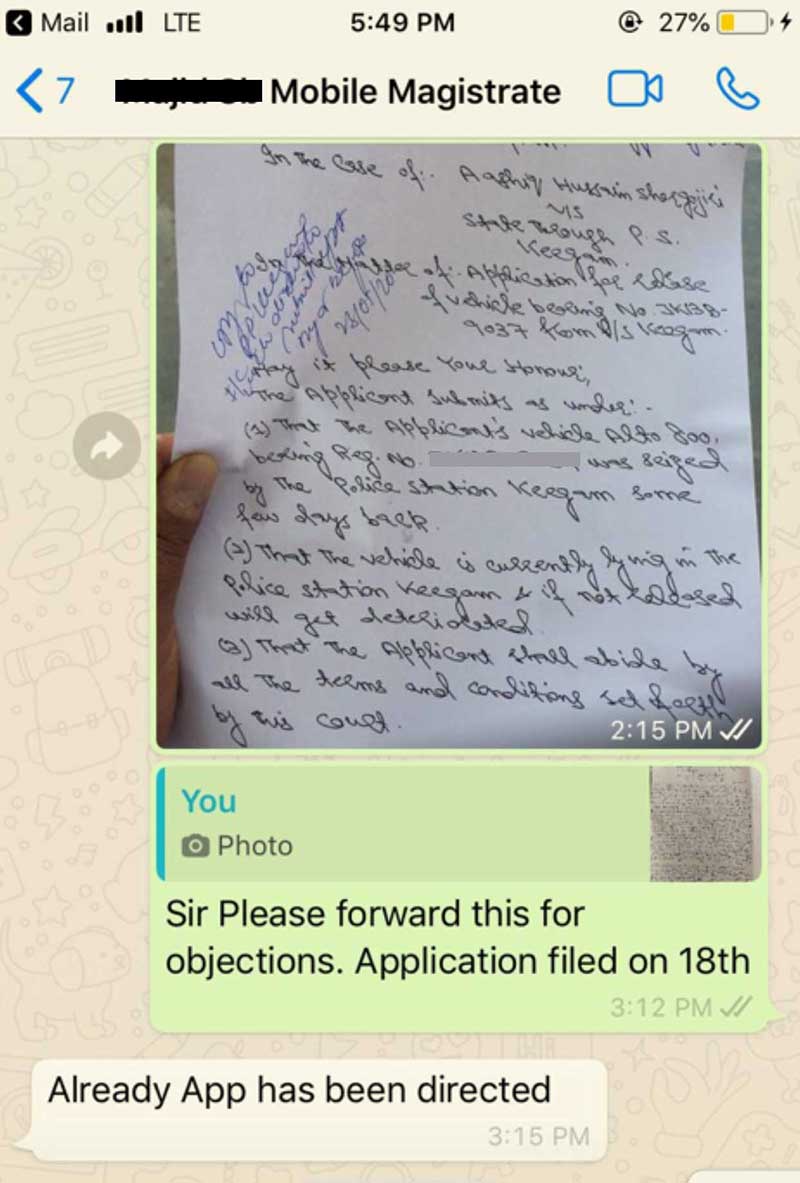

Although the legal basis of internet restrictions were rarely made public prior to the Bhasin judgment, in practice police authorities issued oral or tersely worded one line written directives to Internet Service Providers (ISP) instructing them to summarily restrict or suspend operations, and to file ‘compliance reports’. An example of such secretive, arbitrary and unlawful orders issued by the Jammu & Kashmir Police, as a ‘preventive measure to avoid any law and order problems and passing of rumours by miscreants/anti national elements’ was documented by Amnesty International during the course of an earlier prolonged internet shutdown and social media ban in 2016-2017. Such orders are also subject to official deniability: in response to a Right to Information query, asking for copies of orders which formed the basis of the shutdowns of internet and telephone services in July 2016, both the Home Department, Jammu & Kashmir (in charge of the Police) and the Divisional Commissioner, Kashmir (the highest executive authority in the Kashmir districts) stated that no such orders were RTI Responses Home/ISA/2017/RTI/507 and Div.Com/RA-RTI/08/2017, on file with JKCCSissued by their office.

Data Source KSCAN Letter to WHO Dir Gen, 25/03/2020; also Lifewire, quoted in letter

Data Source KSCAN Letter to WHO Dir Gen, 25/03/2020; also Lifewire, quoted in letter

The entrenched control that police authorities nonetheless continue to exercise over internet access is underlined by the practice of compelling users to sign ‘personal bonds’ of good behaviour. This is a precondition to restoring internet access for ‘verified’ bureaucrats, businessmen, and even university students after conducting background checks. The bonds imposed six conditionalities: among them the requirement that social media would not be accessed, internet usage would be for "business purposes" only, "contents" and "infrastructure" of internet usage would be shared as and when required by the "security agencies", and no encrypted files containing videos or photos would be uploaded. The Wire reported that the final clearance to restore internet connections was given by the office of the Inspector General of Police (IGP), the highest ranking police official in the region. The IGP also continues to be vested with the powers of an official authorised to pass emergency suspension orders on precautionary public safety grounds, under the Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services (Public Emergency or Public Safety) Rules, 2017 (through which internet restrictions are now legally imposed, after the judgment in the Anuradha Bhasin case).

During the course of hearings in the Anuradha Bhasin case, despite repeated demands by the Petitioner and multiple ‘opportunities’ from the Supreme Court, the government of Jammu & Kashmir failed to disclose the specific legal basis and grounds for the complete and indefinite telecommunications shutdown and continuing restrictions. The only public notifications finally placed before the court were two vaguely worded "sample" orders issued by District Magistrates in two districts under Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973, without outlining how these were related to the indefinite and complete internet shutdown across all Kashmir districts, how many other similar orders were passed, by whom, when or under what circumstances.

Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code is routinely used in Jammu & Kashmir to impose curfew-like restrictions, particularly on free movement and public assembly. The section, whose origins lie in colonial policing, empower a District Magistrate, a Sub-divisional Magistrate, or any other Executive Magistrate specially empowered by the government to ‘direct any person to abstain from a certain act’ or to ‘take certain orders with respect to certain property in his possession or under his management’, if the Magistrate considers that such direction is ‘likely to prevent, or tends to prevent, obstruction, annoyance or injury to any person lawfully employed, or danger to human life, health or safety, or a disturbance of the public tranquility, or a riot, of an affray.’ Where the circumstances do not admit serving of notice to the person against whom the order is sanctioned this order can be passed ex parte. While no such order can ordinarily remain in force for more than two months, if the government considers it necessary so as to prevent danger to human life, health or safety, or to prevent a riot or any affray, the order can be extended for a period not exceeding six months.

The Software Freedom Law Centre, has documented how Section 144 orders were routinely used as a means of instituting internet shutdowns across India prior to the enactment of the Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services (Public Emergency or Public Safety) Rules in 2017. While the Supreme Court of India has held that the government should only use Section 144 as ‘a last resort’ during emergencies, in February 2016, in the case of Gaurav Sureshbhai Vyas v. State of Gujarat, the Gujarat High Court upheld the power of the state governments to restrict access to the internet under Section 144, observing that "It becomes very necessary sometimes for law and order."

In September 2019, while Kashmir was still reeling under a complete internet and communication shutdown, and the Supreme Court was hearing the Anuradha Bhasin petition on the constitutionality of the blackout, the High Court of Kerala in Faheema Shirin v. State of Kerala upheld the right to access the internet as a fundamental right. The court interpreted this right

ANURADHA BHASIN VS UNION OF INDIA

A week after the internet and telecommunications shutdown was imposed, Anuradha Bhasin, the editor of Kashmir Times, the oldest English language newspaper in Jammu & Kashmir, filed a petition in the Supreme Court of India challenging the unconstitutional restrictions imposed on her fundamental rights of freedom of speech and profession, on account of the complete and indefinite media and internet blackout and curfew-like restrictions.

The hearings stretched over five months, with state respondents repeatedly seeking (and being granted) adjournments citing national security, and the need to ensure a return to ‘normalcy’, before rights were adjudicated or any orders passed. Each time the matter came up for hearing the state either denied the existence of de jure restrictions, detailed the existence of temporary phone and internet facilities, or stated that restrictions were being eased in a phased manner, even as the Petitioner pressed for urgent orders, asserting the continuing nature of the rights violations on the ground.

Petitioners advanced arguments including the unconstitutionality of an ‘undeclared emergency’; the disproportionate, arbitrary, and impermissible nature of the restrictions on free speech and movement, and the illegality of executive actions in the absence of official orders or public notice. The state maintained that the restrictions were ‘necessary and proportionate’ on grounds of national security, and were based on executive apprehensions of threats to national security and public order. They accounted for the restrictions on mobility under executive powers of District Magistrates under Section 144, Criminal Procedure Code, but failed to provide any legal basis for the internet and telecommunications disruptions, other than a handful of pro-forma "sample" Section 144 orders.

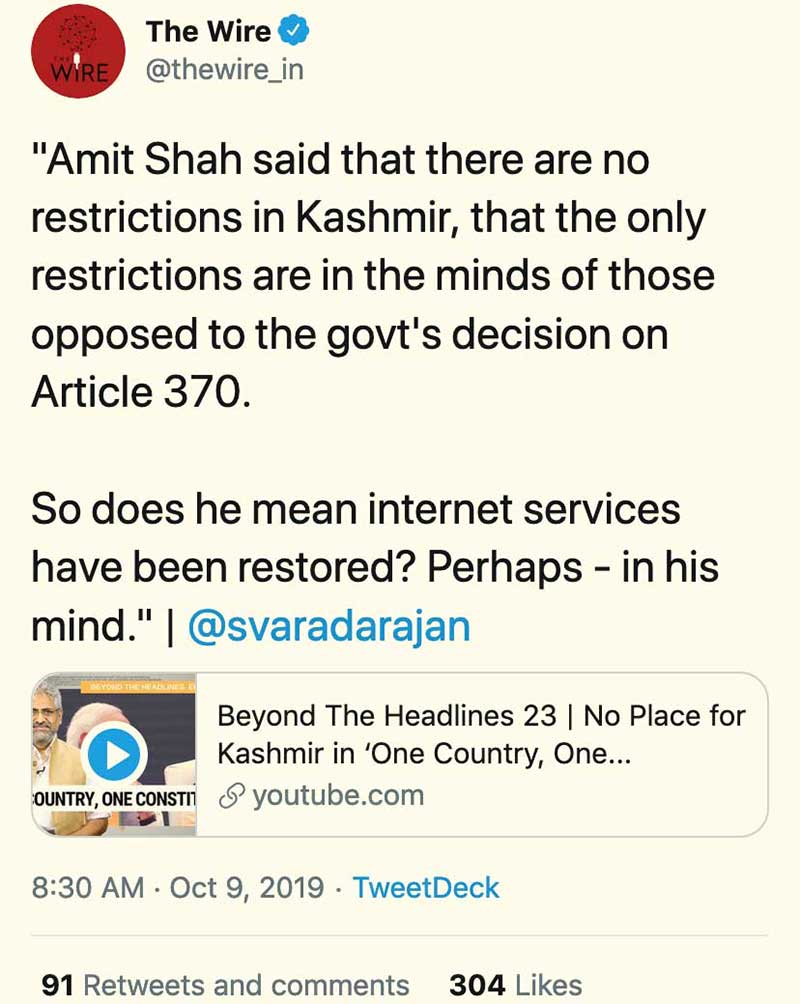

The final judgment centered on the question of the restrictions on the internet: the Court affirmed Bhasin’s right to carry on her trade and profession, and to free speech and expression over the internet, but did not rule on whether there was a right to internet access per se. It also reiterated the test of proportionality and necessity of restrictions on national security grounds. It held that restrictions must be reasoned, specific, temporary and minimally disruptive, and that blanket and indefinite shutdowns are unconstitutional. However, it did not apply this test to the situation of the continuing network disruptions in Kashmir and declare them unconstitutional. Instead it held that future internet restrictions must be publicly notified, specific, and subject to periodic review by an executive committee as statutorily mandated under the Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services (Public Emergency or Public Safety) Rules, 2017. This inaugurated a new phase of the internet blockade and of surveillance in Kashmir, which continues till today, based on routine executive orders that prohibit access to particular websites and throttle internet speeds while citing grounds of national sovereignty and public order.

to fall under a person’s right to education and right to privacy, which falls under Article 21 of the Indian constitution. Three months later, while Kashmir was still under internet restrictions, and even as the hearings in the Supreme Court case dragged on, the High Court of Assam passed an interim order directing the government of Assam to restore internet services, blocked during protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act. (The court stated that there was a lack of material placed on record that evidenced a law and order problem that might result from permitting unblocking of internet services.) In an article in The Wire, human rights lawyer Mishi Chaudhuri notes the continuing existence of this practice, drawing attention to the spate of Section 144 orders for blocking of the internet used recently by Indian authorities to enact ad-hoc communications shutdown in the context of widespread public protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act.

These unchecked executive powers are a means of bypassing the more stringent legal mechanisms for internet blocking laid down under Section 69 A of the Information Technology Act, 2000 and the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885. Under the Information Technology Act, a content removal or blocking request can be sent by authorised officers in the Union Government, on grounds of "the interest of the sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of India, the security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states or public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of any cognisable offence relating to the above." This is the section upheld by the Indian Supreme Court in the case of Shreya Singhal v Union of India. Technology researchers Torsha Sarkar and Gushabad Grover, point out that "the blocking rules envisage the process of blocking to be largely executive-driven and require strict confidentiality to be maintained around the issuance of blocking orders. This shrouds content takedown orders in a cloak of secrecy and makes it impossible for users and content creators to ascertain the legitimacy or legality of the government action in any instance of blocking." Such opaque and arbitrary legal procedures have been used extensively against service providers as well as thousands of users in the Kashmir context. Vaguely worded take down notices are issued to internet based and social media intermediaries (such as Twitter and Facebook), as the Committee to Protect Journalists noted with alarm in October 2019.

Section 5(2) of the Indian Telegraph Act, 1885 allows authorized officers to block the transmission of any telegraphic message or class of messages (which has been amended to include internet and telecommunications services) during a public emergency or in the interest of public safety. In April 2017, this law and the 2007 rules enacted under it were cited by the state government as the basis of a sweeping social media ban of one month in Kashmir valley, placed on 22 websites. The Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services (Public Emergency or Public Safety) Rules, 2017 were enacted in August 2017, under the Indian Telegraph Act. According to these rules, an order for suspension of telecom services can be made by a ‘competent authority’. The ‘competent authority’ in case of the Government of India is the Secretary in the Ministry of Home Affairs. In case of a State Government, the competent authority is the Secretary to the State Government in-charge of the Home Department. After the abrogation of Article 370, in the directly ruled Union Territories of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh, (which have in any case been under ‘President’s Rule’ since June 2018, that is, a state of emergency where administration is through a Union executive rather than the state legislature) the Indian Union’s Ministry of Home Affairs continues to be the authority in charge.

The rules mandate that in order to be valid an order passed by the competent authority must "contain reasons for such direction" and a copy of the order will be forwarded to a Review Committee by the next working day. The Review Committee must meet within five working days of the issuance of order and record its findings on the suspension order as to whether it is in accordance with the provisions of sub-section (2) of section 5 of the Indian Telegraph Act. Following the Supreme Court judgement in the Anuradha Bhasin case, government orders that only perfunctorily conform to these statutory requirements have been routinely passed by the administration, the latest of which extends the restrictions of Internet speeds to August 19th 2020. In the Foundation of Media Professionals case, under orders of the Supreme Court a special executive committee has been set up for the purpose of reviewing internet restriction orders passed in Kashmir, given the context of the Covid-19 pandemic.

surveillance, privacy and the criminalisation of online speech

Digital rights including the right to privacy of internet users in Kashmir is also severely harmed by the dense military-intelligence and counter-insurgency grid, which enables multiple "security agencies" to engage in covert monitoring and interception operations with little to no oversight, public information or transparency. Aspects of this normally secretive world came into view recently when news outlets including the Indian Express reported on the police’s abilities to monitor and trace Covid-19 contacts, including through phone and internet based call and messaging services, GPS tracking and ATM withdrawals, all the while relying on existing infrastructure and data bases. In a recent court hearing in the petition filed by the Foundation for Media Professionals, which asks for the restoration of unrestricted internet in light of the Covid pandemic, the Solicitor General of India, tangentially referred to the prevailing practices of covert mass surveillance when he justified the continuing restrictions on 4G internet on security grounds saying access had already been granted to "land lines which are traceable and cannot be misused for anti-national activities."

Under Indian law, while the Indian Telegraph Act enables executive authorities to carry out telephone surveillance, electronic surveillance may be authorised only under the Information Technology Act. The landmark judgements of the Supreme Court in People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India, and K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India recognised the fundamental right to privacy, and laid down the constitutional test for the strict scrutiny of privacy invasions on grounds of proportionality. Despite this, a Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) notification of December 2018 authorised extensive powers to ten federal agencies to intercept and monitor communications. The permissible grounds for such surveillance are extremely broad, drawing from constitutional provisions pertaining to restrictions on free speech and expression, including the maintenance of "friendly relations with foreign States" or "sovereignty and integrity of India."

In Kashmir, legal restrictions and criminal sanctions have been used in conjunction with extra-legal and unlawful censorship and surveillance measures to target social media activists and commentators. For instance, Section 66A of the Information Technology Act 2000 contains a provision prohibiting the dissemination of information that a person knows to be false by means of a computer resource or a communication device ‘for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience, danger, obstruction, insult, injury, criminal intimidation, enmity, hatred, or ill will.’ Though this broadly worded provision has been struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, it continues to be widely used against social media users, in tandem with police complaints under other widely criticised criminal incitement and hate speech laws under the Indian Penal Code (IPC), such as "exciting disaffection" against the state (Section 124 A, IPC), "promoting enmity between different groups" (Section 153 A, IPC), "incitement to an offence" (Section 505, IPC) and "disobedience of an official order" (Section 188, IPC).

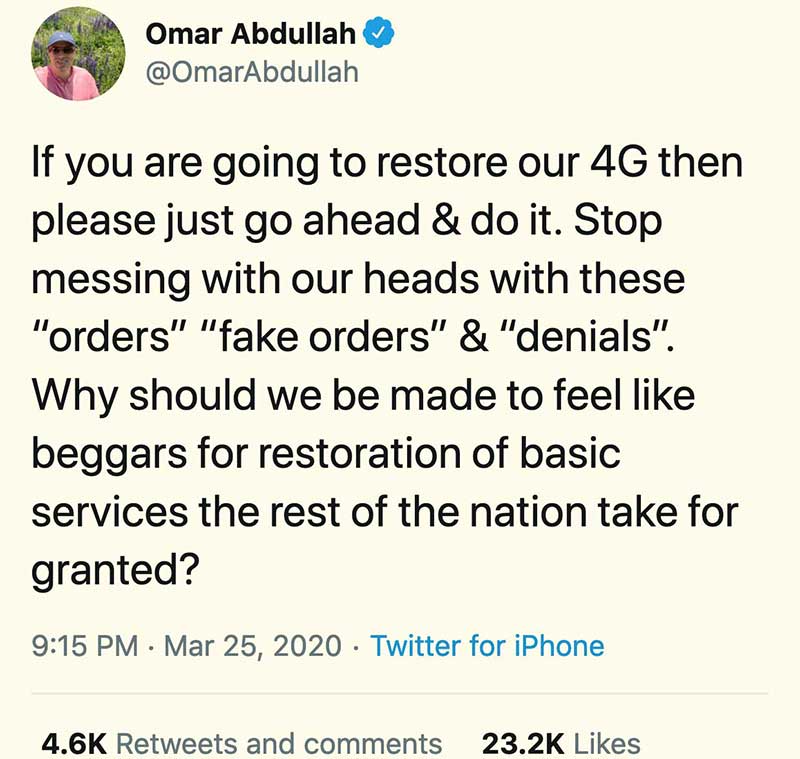

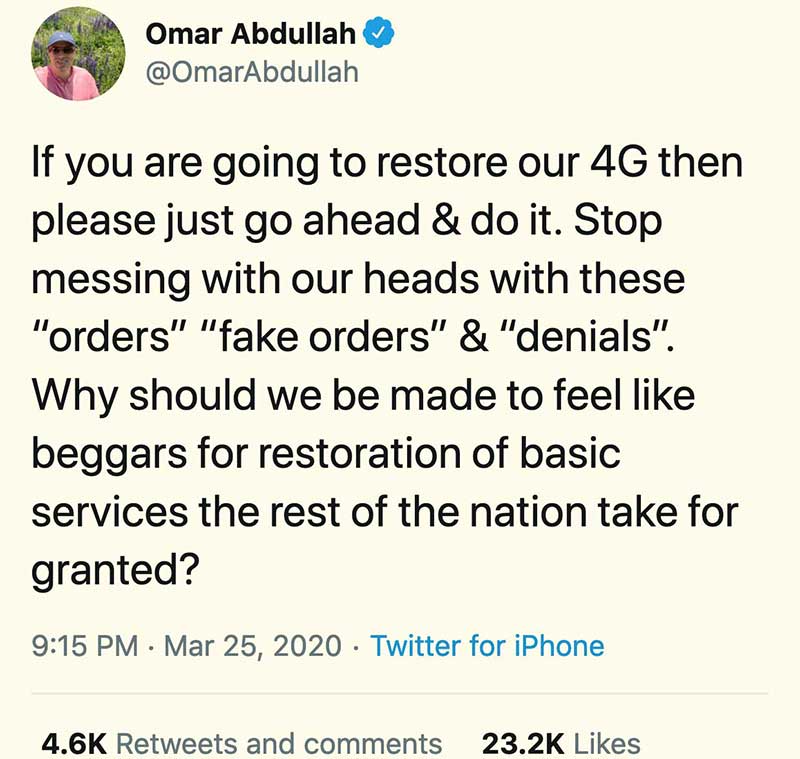

The Jammu & Kashmir Public Safety Act, 1978, a preventive detention law that allows for imprisonment without trial or charges for up to two years, on grounds of public order and national security, has also been extensively used to target social media users for their posts, including in the recent case of the preventive detention of former Chief Minister Omar Abdullah for seven months. In a further criminalising move, after the partial restoration of the internet in January 2020, cyber crimes police have been increasingly resorting to the use of provisions under the draconian anti-terror law, Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1968 to target and terrorise social media users and journalists. This consistent pattern of using criminal laws to target online speech and journalism has been noted with concern in a recent letter addressed to the Government of India by three UN Human Rights experts.

These legal precedents and enactments relating to internet governance in Kashmir must be contextualised within a generalised climate of entrenched impunity and repressive media laws, including for instance The Jammu & Kashmir State Press and Publication Act, 1932, which empowers the government to "seize any printing press, used for the purpose of printing or publishing any newspaper, book, or other document, containing any words, signs or visible representation which incites or encourages or tends to incite or encourage, the commission of any offence of murder or any cognizable offence involving violence[...]; seduces any military force officer or soldier or any police officer from his allegiance to his duty." This provision was used in October 2016 to impose a three-month ban on the publication of a Srinagar based newspaper, Kashmir Reader. Instances of illegal prohibitions and expansive restrictions on popular mediums of communication and broadcast, including cable news television, short messaging services (SMS) and mobile internet services have been common since 2008, after the armed rebellion in the region had largely given way to mass civilian protests and political mobilisations. For example, on May 5th 2017, the Jammu & Kashmir government ordered all Deputy Commissioners of the state to take action against the transmission of 34 TV channels, including all news, sports and religious channels broadcast from Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, citing their potential to ‘incite violence and create law and order situation’ under the extensive emergency powers of the Cable Television Networks (Regulation) Act, 1995. This law was also used in 2010, when news and current affairs programmes were prohibited on channels operated by local cable operators. The ban continues to be in place.

the right to access the internet

In April 2020, during a spate of heavy artillery shelling between India and Pakistan, residents of Panzgam, a village 20 kilometres away from the massively fortified border inside Indian territory, staged protests against the stationing and firing of artillery guns from a nearby military encampment in the playing fields of their village. Videos and images of women and elderly villagers confronting the military men, with their homes and the 155 mm Bofors artillery guns as a backdrop, began to circulate on social media. Mobile data services were immediately shut down in the entire district, through an emergency order issued by the IGP Kashmir, citing the standard grounds of the "likelihood of misuse of data services by anti-national elements for uploading inciting/objectionable material having the potential of disturbing the public order." While the official order mentioned a suspension of services for six hours, the shutdown inevitably continued for several days.

FOUNDATION FOR MEDIA PROFESSIONALS

VS UNION TERRITORY OF JAMMU & KASHMIR

In April, 2020 The foundation for Media Professionals (FMP), a New Delhi based association of journalists, Soayib Qureshi, a lawyer from Kashmir, and the Private Schools Association of Jammu & Kashmir, filed a joint petition before the Supreme Court of India, seeking restoration of 4G internet in the region in context of the Covid pandemic and the consequent nationwide lockdown.

The Petitioners sought the quashing of the latest executive order restricting internet in the union territory of Jammu & Kashmir, which they saw as unconstitutional, and asked for the restoration of 4G internet service. They contended that the suspension of internet services was a violation of their fundamental rights to health, education, freedom of speech, freedom of business and access to justice. The first petitioner, FMP, submitted affidavits by doctors, journalists, teachers, students, lawyers and business people from the region, as well as the testimony of a technology expert, to demonstrate the importance of 4G internet service. They asserted that the Respondent state had failed to comply with the constitutional standards for restricting internet access laid down by the Supreme Court in the Anuradha Bhasin case and the statutory requirements of the Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services (Public Emergency or Public Safety) Rules, 2017 (Telecom Suspension Rules).

The Respondent state, represented by the Attorney General of India, focused on the necessity of an internet shutdown in defence of national security. They submitted that matters of national security lay exclusively in the legislative domain of ‘policy making’ and must not be subject to judicial review. They submitted that the "continuing insurgency in the region, the spreading of fake news to incite violence, etc." required an ongoing restriction of internet services. They stated that as no restriction was imposed over fixed line internet, information relating to Covid-19 could be received through internet as well other forms of print and electronic media, radio broadcasts, and social media.

In its judgment the Supreme Court primarily upheld the necessity of balancing national security concerns against the fundamental rights of citizens. It reiterated the importance of the test of proportionality and necessity of restrictions in order to minimize the impact on the enjoyment of fundamental rights. Despite acknowledging that the blanket restrictions across Jammu & Kashmir did not conform to the proportionality requirements in the Anuradha Bhasin case, the Court did not strike down the restriction order. Instead, keeping in mind national security implications, the Court directed that a special Review Committee consisting of officials from the state and Union executive, should examine the Petitioner’s contentions with regard to the extent and duration of the restrictions. (In effect this meant that the authorities empowered to pass the restriction orders were now to review those same decisions.) In June 2020, the Petitioners further pointed out that the government had failed to constitute the special Review Committee as directed by the Supreme Court, and filed a contempt petition for failure to comply with its directions. Hearings in the contempt of court proceedings are ongoing.

Amidst the internet blackout and the complete restrictions on mobility imposed in the wake of the Covid lockdown, the border war continued. The placement of the artillery guns had brought the village into the direct line of Pakistani bombardment, and amounted to using them as human shields, a grave violation of human rights law and the laws of war. Three civilians, a woman and two children aged 16 and 8 were killed, and a 78 year old man injured. Middle East Eye reported that "Villagers said that not only were they placed in the direct line of retaliatory attacks but the deafening sound from Bofors artillery guns had damaged homes, terrorised children and turned the quiet village into a war zone."

Internet shutdowns in belligerent or politically violent contexts often function as a means of preventing international monitoring of systemic repression and war crimes. A report by Jan Rydzak for the Global Network Initiative (GNI) that details the human rights impacts of network disruptions states that "[n]etwork disruptions and shutdowns provide an invisibility cloak for violence as well as gross violations of human rights and/or the laws of war. Shutdowns enable governments and non-state actors to conceal violations of the right to bodily (or physical) integrity and security of persons behind a digital smokescreen." In Kashmir, local human rights groups like the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP), which advocates for rights of victims of enforced disappearance, were unable to hold their iconic public monthly sit-ins in Srinagar. They lost all connection with families they work with. These connections, representing years of painstaking work in the community, were not restored even after the mobile services started working as most people had lost their old phone connections, and had changed their connection from prepaid to postpaid mobile services.

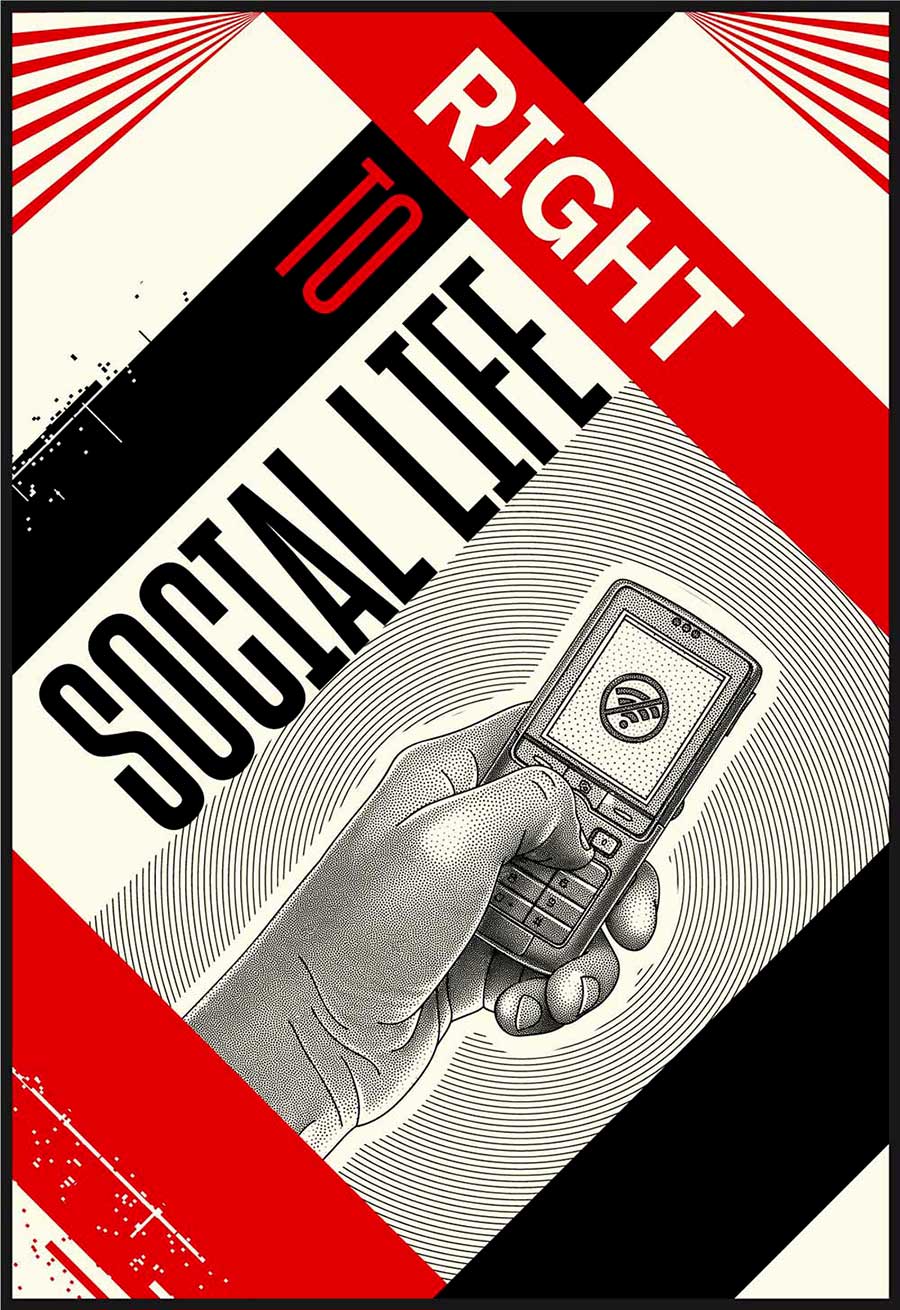

Recent developments in International Human Rights law affirm that the right to access internet and communications technology is not a privilege but a core component of rights to freedom of expression and opinion, and an enabler of other fundamental human rights, cutting across the public and private dimensions of human security and dignity, as well as social, political and economic life. Governments therefore have a responsibility to ensure that Internet access is available, and they may not unreasonably restrict an individual’s access to the Internet.

A 2011 report presented by Frank La Rue, the UN Special Rapporteur ‘on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression’, concluded that disconnecting people from the internet is a human rights violation and against international law. The Special Rapporteur called upon all states to ensure that internet access is maintained at all times, including during times of political unrest, asserting that shutting it off in its entirety would not meet the requirement of proportionality of restrictive measures. The UN Human Rights Council passed a non-binding resolution on 27 June 2016, unequivocally condemning measures to "intentionally prevent or disrupt access to or dissemination of information online in violation of international human rights law" and called on all States "to refrain from and cease such measures." The resolution also affirms that "the same rights that people have offline must also be protected online, in particular freedom of expression."

While international human rights law recognises that governments may derogate from human rights obligations under exceptional situations of public emergencies and conditions of existential threat or grave peril, such restrictions must be narrowly construed and fulfil the tests of necessity and proportionality. The 2017 Report of the Special Rapporteur ‘on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression’ is categorical in its view that large scale, routine, shutdowns on vaguely defined national security grounds, of the sort that have been endemic to Jammu & Kashmir, are illegal: "Network shutdowns invariably fail to meet the standard of necessity. Necessity requires a showing that shutdowns would achieve their stated purpose, which in fact they often jeopardize [...] Duration and geographical scope may vary, but shutdowns are generally disproportionate. Affected users are cut off from emergency services and health information, mobile banking and e-commerce, transportation, school classes, voting and election monitoring, reporting on major crises and events, and human rights investigations. Given the number of essential activities and services they affect, shutdowns restrict expression and interfere with other fundamental rights." Commenting on the earlier internet shutdown in Kashmir in 2016-2017, two UN human rights experts, David Kaye and Michael Forst, issued a statement asking for the internet to be immediately restored, stating that "The scope of these restrictions has a significantly disproportionate impact on the fundamental rights of everyone in Kashmir, undermining the Government’s stated aim of preventing dissemination of information that could lead to violence"

Government policies accorded preferential access to government owned service providers like Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited (BSNL), as well private actors such as the Reliance group

The communication blockade in Kashmir also raises essential questions of the human rights responsibilities of private corporations, particular digital access providers. In his 2017 report to the Office of the High Commision on Human Rights, UN Special Rapporteur David Kaye specifically addressed this issue stating "What governments demand of private actors, and how those actors respond, can cripple the exchange of information; limit journalists’ capacity to investigate securely; deter whistle-blowers and human rights defenders." Unlawful state actions blockading the internet enabled telecommunication and internet service providers to exploit the vulnerability and helplessness of Kashmiris.

On the basis of TRAI data the Business Standard estimated that Telecom operators’ suffered losses worth Rs 40-50 million per day. Government policies accorded preferential access to government owned service providers like Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited (BSNL), as well as private actors such as the Reliance group. After 45 days of a complete communications blackout, BSNL landline phones were the first to be restored. Despite the continuing restrictions on mobility people started queuing up to get new BSNL landline connections, or attempted to restore connections that had largely been surrendered after the entry of mobile phones. The limited relief provided by restoring BSNL landline service can be gauged by the fact that for a population of approximately 8 million in the Kashmir valley districts, there were only 45,000 BSNL landline connections till August 5th 2019. A senior BSNL officer said the company has provided over 14,000 additional landline connections in the valley since the communication clampdown.

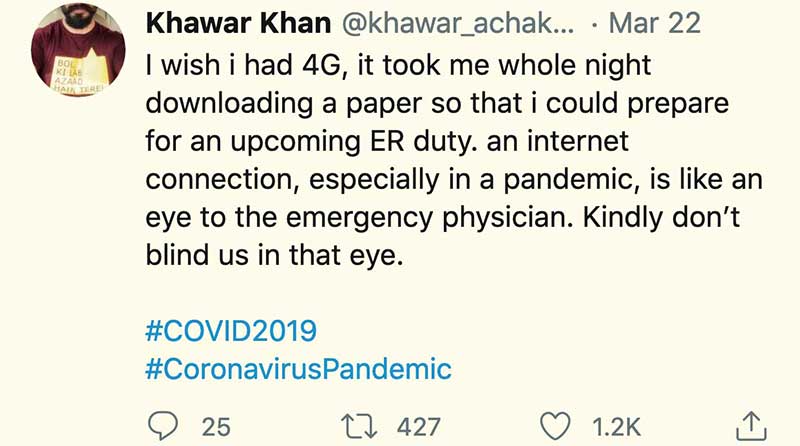

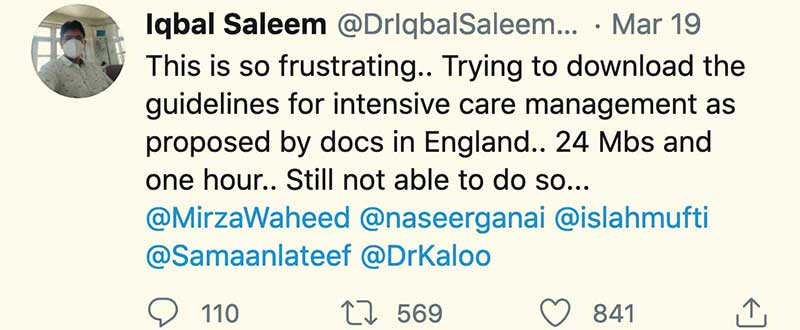

A day after a communication blockade was imposed Jio-Fibre, a fibre cable internet service launched by the Reliance group, began operations in Jammu introducing high speed postpaid services via fibre cable in the region. According to data by TRAI, in December 2019 only Jio was able to add to its subscriber base in Jammu & Kashmir, with its dominance of the postpaid segment through heavily discounted schemes. Citizen Matters also reported on the basis of TRAI data that out of 26,000 prepaid connections, 20,000 subscribers switched over to post-paid subscriptions, and once mobile internet was restored, a majority shifted to Jio postpaid numbers. However despite the disruption and lack of services all companies continued to charge subscribers for all services, Andalou Agency reported, including for 4G internet, In keeping with the concerns expressed by the UN experts cited earlier, human rights groups such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Reporters Without Borders have condemned the disruption of network connectivity in Jammu & Kashmir, highlighting the egregious violations of rights and freedoms such disruption entails and demanding full restoration of network connectivity. These demands have intensified in light of the Covid-19 pandemic, given the grave implications of throttling the internet for medical and humanitarian work. In April 2020 a consortium of digital and human rights groups led by Access Now, wrote to the Government of India reiterating their call for the full restoration of internet connectivity in Jammu & Kashmir. "The absence of 4G internet has particularly hindered the work of health professionals who are on the front lines combating this global pandemic. Doctors in Jammu & Kashmir are struggling to access important information, often waiting hours to download and access information such as guidelines for intensive care management of the virus and best practices recommended by the WHO. The restriction of high-speed internet access has also impeded the work of human rights defenders, journalists, and other actors working in the region," the letter read.

A report by Global Network Initiative argues that "Large-scale disruptions constitute a radical form of digital repression—one that curbs multiple rights established in international treaties while undermining local, regional, and national economies." In discussing the issue of the right to equality and the global trend towards digital discrimination against disenfranchised communities, the report goes on to say, "Shutdowns may constitute a targeted form of digital repression that disproportionately affects a marginalized community and thus constitutes collective punishment." This assessment of the targeted denial of internet as a systemic form of discrimination and the violation of rights rings true in the case of Kashmir, given its Muslim majority population and a long history of political repression and atrocities.

The digital siege in Kashmir raises important questions of human right violations, and collective punishment, in the context of intense and organised political violence amounting to an armed conflict, where not just international human rights law, but the framework of international humanitarian laws applies as well. International humanitarian law is premised on a distinction between civilian and military targets and objectives, in addition to specifying rules about the necessity and proportionality of military actions. In the digital age, the internet and communications network are vital civilian infrastructure, as essential to everyday life as highways or the postal system were when these rules were first framed. Prolonged internet disruptions and attacks on the internet network are similar to other kinds of disproportionate collective punishment and impermissible forms of civilian targeting, such as sieges and military blockades.

The Tallin Manual 2.0, an authoritative treatise by legal experts on the international law applicable to cyber warfare is quite categorical that "an attack that shuts down a network shared by civilians would be unlawful in the same way carpet bombing of cities is prohibited. Further, shutting down the internet would amount to the "collective punishment" prohibited by Additional Protocol I of the Geneva Convention. Accordingly, the Tallinn experts have concluded that shutting down internet access amounts to "impermissible brutality." In an interview addressing the Kashmir shutdown, the UN Special Rapporteur for Free Speech and Expression, David Kaye underlined this broader view when he stated "I would like to see the political bodies, including the [UN] Security Council and General Assembly, recognise that assaults on communications amount not only to a violation of human rights, as they have in the past, but also potential threats to peace and security."

The promise of lasting peace, freedom and justice for the people of Kashmir is inextricably tied to digital and human rights in the region.

international covenant on economic, social and cultural rights

article 6

1 The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right to work, which includes the right of everyone to the opportunity to gain his living by work which he freely chooses or accepts, and will take appropriate steps to safeguard this right.

2 The steps to be taken by a State Party to the present Covenant to achieve the full realization of this right shall include technical and vocational guidance and training programmes, policies and techniques to achieve steady economic, social and cultural development and full and productive employment under conditions safeguarding fundamental political and economic freedoms to the individual.

enterprise runs aground

In Jammu & Kashmir the months between August and December are critical for tourism, horticulture, and handicrafts, which together constitute a major segment of its economy. The shutdown of August 2019 had severe economic consequences and the losses suffered by various businesses in the five months after were estimated by the Kashmir Chambers of Commerce and Industry (KCCI) at Rs 178.78 billion. The KCCI report also estimated that more than 500,000 people lost their jobs in the valley in the same period.

The communications blockade that accompanied the lockdown also made apparent how reliant business, trade and manufacture in Kashmir had become on the internet. A report from the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER 2018) had previously drawn attention to the fact that internet curbs between 2012-2017 had cost Kashmir’s economy Rs 40 billion. In comparison the first five months of the 2019 shutdown cost the economy more than the intermittent shutdowns of five previous years.

BANKING AND FINANCE

Accustomed to the frequent disruptions in physical movement in the region, including those caused by curfews and hartals, small business and trade in J&K had quickly adapted to e-banking. J&K Bank, a prominent bank in the region, first introduced e-banking around 2007, and its convenience and cost-effectiveness can be measured by the fact that almost 1.1 million traders and businessmen have signed up for these services with the bank. Most retail shopkeepers in Kashmir have also moved their cash collection to Point-of-Sale machines, which rely on mobile internet. One sharp indicator of the distress caused by the shutdown was the increase in Response to RTI filed by JKCCS: JKB/ZKC1/RTI/2020-31 received 07.04.2020defaults in instalment payments to the J&K Bank: they rose from 125 before August 5th, 2019 to 11,578 in September 2019.

For the retail consumer the internet shutdown disabled access to all modes of netbanking, as well as various online payment portals, including mPay and Paytm. For those who had children studying outside Kashmir, or family members in hospitals far away from home, this meant that the speedy transfer of money through online services came to a dead halt. Locally too there were immediate repercussions. "The number of utility bills we used to handle had dropped significantly as people would pay these online," a JK Bank official told the Economic Times, "But now everyone has to come to the bank, resulting in long queues, which has affected our productivity also."

For those who had children studying outside Kashmir, or family members in hospitals far away from home, this meant that the speedy transfer of money through online services came to a dead halt.

This loss of e-banking had other direct costs. For any bank the average ‘cost per transaction’— depositing cash or a cheque, or transferring money—is approximately Rs 70-80. Conducted via ATM, this cost drops to Rs 18-20. Online banking brings per transaction costs down to around Rs 4-5. In J&K Bank where 80% of the transactions are to do with funds transfer and cash (withdrawal or deposit), e-banking is more than a convenience for retail customers. These savings play a crucial role in shoring up the bottom-line of the Bank, Telephone interview / Ejouz Ayoub, J&K Bank / 03.05.2020JKCCS researchers learnt.

Operating within a conflict zone has provided bankers in Kashmir with some training for such internet shutdowns. However the August 2019 shutdown was unprecedented in the complete disabling of broadband, mobile telephones as well as landline phones. Without access to email or SMS, J&K Bank had to place notices in newspapers to reach out to their customers. (Even to place the advertisement someone had to physically carry the material on a pen-drive to the newspaper office.) Within the bank, only the controlling office had a leased line, and working internet. For the rest, drivers and peons were assigned the job of carrying information from one office to another, and from the headquarter to different zones. Eventually the Bank had to revive a long-neglected intranet, a privately owned network for communication within the organisation. In order to access important clients in other cities and across the world, officials in J&K Bank were reaching out to their colleagues in other branches. Until the end of October, they were running parallel offices in Mumbai and Delhi, Telephone interview / Ejouz Ayoub, J&K Bank / 03.05.2020JKCCS researchers were told, incurring huge costs, and facing the loss of many clients due to their inability to provide services.

HANDICRAFTS

The internet siege caused major disruptions in the handicrafts sector, a major industry in Kashmir with more than 250,000 registered weavers and artisans. The President of KCCI estimated that 60,000 to 70,000 of these artisans had been rendered unemployed. For the handicrafts industry the months of August and September are the main period when orders flow in from all across the world, in preparation for the winter and Christmas holiday season. Kashmir Box, an online store for Kashmiri handicrafts, which ships local products to over 50 countries worldwide, reported lost orders to the tune of $420,000. "We’ve seen more than 400 shutdowns," founder Muheet Mehraj told the New York Times, "this has been the worst of them all." Incoming orders could not be received, he added, and communicating with suppliers was impossible – with 25 employees idle, the extended shutdown would soon put all of them out of work. Omaira, co-owner of an online venture called Craft World Kashmir has been working to revive the art of crochet. Without the overheads of a retail presence she has developed a vast following on social media sites with nearly 40,000 followers (and potential buyers) on Twitter alone. Without orders she was unable to pay any of her employees during the shutdown, she told Newsclick. "Artisans work on looms, do embroidery at home and all of them are dependent on a constant supply of material and work orders," Pervaiz Ahmed Bhat, President of Artisan Rehabilitation Forum told Outlook, "What happened due to the lockdown and communication blockade is that artisans had no contact with suppliers and they couldn’t complete their work," he said. The President of the Chamber of Commerce and Industries Kashmir (CCIK), Ghulam Mohiuddin Khan, estimated a loss of Rs 10 billion to the industry since August 5th. "We couldn’t even send photographs of sample products over email or WhatsApp to customers and prospective buyers outside the state," he told The Wire.

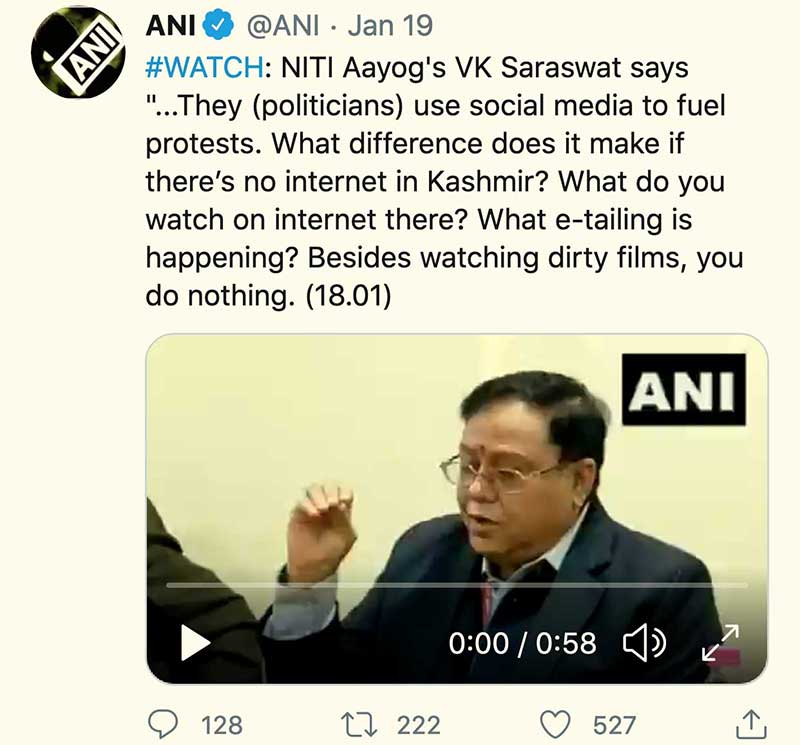

Meanwhile, V K Saraswat, a senior member of the NITI Aayog, the Government of India’s top policy think tank, was reported as saying, "What difference does it make if there’s no internet in Kashmir? What do you watch on internet there? What e-tailing is happening there? Besides watching dirty films, you do nothing there. If there is no internet in Kashmir, it does not have any significant effect on the economy."

TOURISM & TRAVEL

The most severe impact of the internet shutdown in Jammu & Kashmir fell upon the tourism industry. A KCCI report for the first 120 days in 10 districts of Kashmir division alone shows the services sector taking the biggest cumulative hit of Rs 91.91 billion, with job losses estimated at 140,500. Around 1100 hotels had reported zero occupancy (against a normal-year average of 60-70% for the months August to October.) The lockdown also affected thousands employed in operating House Boats, Shikaras, Taxis, as well as those working as Photographers, Pony-wallahs, Guides, in Rafting and Adventure Sports, and other allied services. Apart from Inbound tourists, losses suffered by Outbound Tour Operators were also assessed, with the latter servicing over 40,000 Kashmiris who travel abroad for the Hajj pilgrimage every year. With everything to do with travel—including online visa processing—no longer possible, this too had taken a hit.

Immediately after the August 5th travel advisory was issued, asking tourists and pilgrims to cut short their trips, Business Today reported that flight prices for travelling from Srinagar had sky-rocketed, with airlines such as IndiGo, SpiceJet, GoAir and AirAsia charging between Rs 10,000-22,000 for a one-way direct flight to Jammu (typical prices are around Rs 3000-5000.) With the Internet shutdown in place, travellers from Srinagar were faced with a situation of black marketeering and over-pricing of air tickets, as they could not buy tickets or verify prices online (or even go to the Airport to purchase tickets in person due to the prevailing mobility restrictions.) Kashmir Observer reported that administrative authorities tried to persuade private airlines to open booking counters at the Tourist Reception Centre (TRC) in central Srinagar, which they refused citing logistical issues. Eventually, this task was given to the Tourism Department which in turn allotted counters to seven major private tour operators, leading to widespread customer allegations of irregularities in the allocation, exploitative over pricing, and price manipulations.

Data Source Tourism Dept. J&K Govt, RTI filed by The Wire, Muzamil Bhat & Chitrangada Choudhury, 26/01/2020

Data Source Tourism Dept. J&K Govt, RTI filed by The Wire, Muzamil Bhat & Chitrangada Choudhury, 26/01/2020

HORTICULTURE

J&K exports around 200,000 metric tons of apples every year, most of which is headed to the markets of north India. The horticulture industry as a whole is pegged to be worth around Rs 80-90 billion annually, and contributes 10% of the state’s gross domestic product (GDP). As profitability in the sector has grown, the area under horticulture has gone up steadily over the years. In an area like Sopore, Indiaspend reported, a family with five acres of land under apple trees could get a yield of 5,000 boxes every year, fetching a profit of approximately Rs 500,000.

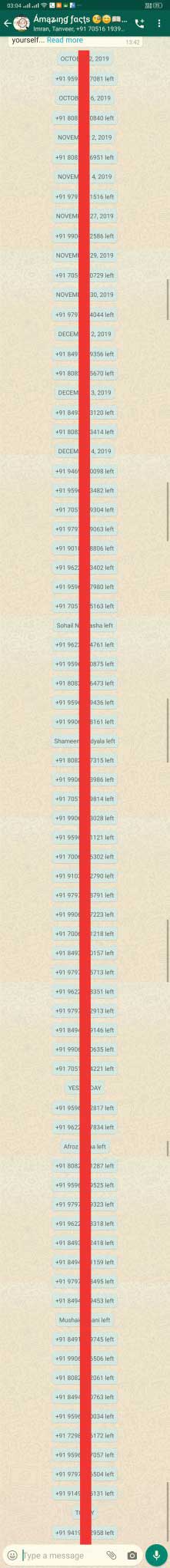

When the internet and communication shutdown was put into place on August 5th 2019, many growers were about ready to go to the market with their produce. "I had the best fruit of my life but I could not coordinate with the market," Shahnawaz Khan of Pinjura, Shopian told Telephone interview / Shahnawaz Khan / 18.06.2020JKCCS researchers. "The buying of fruit is all done through commission agents, most of whom are them in the Azadpur Mandi in Delhi, and the absence of phones made things very difficult. I had to go to the DC office to make calls, but lines were so long that it took me 2-3 days to even make that call," he said, speaking of the facilities set up by the administration to allow phone calls. The loss of Whatsapp access was even more critical for apple growers. They would normally use WhatsApp to send photographs of their produce to commission agents, and depending on the quality would be able to obtain an approximate rate. (An eventual variation of Rs 10-20 on a final price was acceptable for the growers, Shahnawaz pointed out.)

When they had access to the phone and internet, growers had options for selling, negotiating with several traders before dispatching the fruit. In August 2019, with the local Mandi shut and phone communications blocked, the commission agent in Azadpur Mandi, Delhi sold Shahnawaz’s first consignment at Rs 500 (per 10 kg), when it should have sold for anything between Rs 700-1200.

The loss of Whatsapp access was even more critical for apple growers. They would use WhatsApp to send photographs of their produce to commission agents, and depending on the quality would be able to obtain an approximate rate.

It was only in the middle of September, after Shahnawaz’s personal landline got working and he called the agent asking him to transfer the money—and cancel the next deal—that he was able to better it to Rs 750. "The genuine rate for what I gave him should have been at least Rs 1000," Shahnawaz told JKCCS researchers, "If I had internet and phone I could have negotiated and told him I can sell to someone else – could have sent to Bombay or another state, not Delhi."

Other Whatsapp groups are equally important for those in horticulture. In the winter of 2019 the fruit crops suffered heavy losses and fruit trees suffered permanent damage due to the heavy snowfall and the non-availability of weather updates, which are usually made available through Whatsapp. Communications between apple growers in Kashmir and commission agents, as well as with officials from the horticulture department, also rely on the popular messaging service. Scientists from the Sher-i-Kashmir University of Agricultural Science & Technology would also recommend good practices via Whatsapp, including timely suggestions for new techniques of harvesting.

The communications blockade affected the transportation of produce too, as coordinating with truck owners and drivers became difficult. Tariff shot up, and transport that would cost Rs 60-70 per box was now costing Rs 180 per box. Even the simplest of things became difficult, Shahnawaz pointed out, including just finding the truck driver: "I had to constantly go to his house to find him. I went to his house but he was not there and his family said he’s at a shop... I spent half my day looking for the truck driver!"

The Saffron industry in Kashmir also relies heavily on the internet, for it is interlinked with multiple markets for Kashmiri saffron - international, Indian, local Kashmiri, and tourist. In each of these segments the bulk of communications is via WhatsApp or email. Buyers ask for photos and videos of the product and only then make purchases. Iqbal Ahmed Ganai, who is involved in the saffron business in Pampore, told Telephone interview / Iqbal Ahmed Ganai / 24.06.2020JKCCS researchers. "I needed a phone and internet to contact the producers and the clients. Without both, my business was completely gone. Even payments to the producers was online via mPay. After the internet shutdown, we had to give them cheques which made things very difficult because payments were delayed and there was a lot of running around involved. We lost 70% of our sales due to the internet shutdown."

Buyers from Delhi and Gujarat who were accustomed to buy saffron after looking at pictures of the product were reluctant to send large amounts of money without being sure of the material. When phone services restarted many buyers got back in touch with traders like Ganai. "But we could still not send photos so we could not make any sales. Even after 2G started, it did not get better for us as internet speed was too slow to send videos and photos. Sending videos of saffron or of processing the saffron, that is, cleaning and cutting them, was also not possible," he said. Saffron producers also lost business due to their inability to check market rates via trade sites like IndiaMART, which previously enabled them to negotiate their selling price with buyers. Domestic buyers shifted to the competitor, Iranian saffron, which sold for Rs 55,000 per kilogram while Kashmir Saffron, while being of better quality, with higher crocin content, was still selling at Rs 72,000.

Even after 2G started, it did not get better for us as internet speed was too slow to send videos and photos. Sending videos of saffron or of processing the saffron, that is, cleaning and cutting them, was also not possible," he said.

In Kargil, where the apricot trade generates revenue of up to Rs 320 million annually, the produce is normally routed through the horticultural trade of the Kashmir valley. Growers here also faced major losses after the August 5th shutdown, Newsclick reported.

MANUFACTURE

Although Kashmir is not a major industrial zone, manufacturing still generates significant economic activity. The largest of these industrial pockets is at Rangreth, the SIDCO Industrial Estate and Electronics Complex on the outskirts of Srinagar, and houses 193 units spread across 1147 kanals of land (approximately 143 acres). Apart from Cold Storage Units, and spice processing factories (including Kanwal Spices with a turnover of close to Rs 1 billion) it houses several small units that manufacture local essentials, including electric blankets, heaters, and wires. During the Covid-19 crisis several manufacturers located here were drawn in to provide essential supplies, including oxygen cylinders and masks, which continue to be in acute demand due to the pandemic. Several Small & Medium Scale Enterprises working in the Information Technology sector are also located within the Rangreth Estate. (See next section)

For local manufacturers the shutdown of August 2019 came on the back of a series of setbacks that began in September 2014 with unprecedented floods that inundated several industrial areas, shutting them down for close to six months. In July 2016 large-scale public protests in the aftermath of the killing of the militant leader Burhan Wani brought business to a halt for several months. In November 2016 the sudden demonetisation of currency notes caused massive economic dislocation in the consumer base. Finally in July 2017 the shift from the Value Added Tax (VAT) to Goods & Services Tax (GST) caused serious losses to most of these entrepreneurs.

"Our ease of doing business was hampered massively," Nasir Bukhari, manufacturer of electrical cables at the Shalteng Industrial Estate outside Srinagar told Telephone interview / Nasir Hussain Bukhari / 08.05.2020JKCCS researchers. "We relied on WhatsApp and E-mail heavily for communication, for example, even sending a photo of a bill which included quantities and cost of all material." Without the internet the need to physically interact with suppliers of raw materials as well as customers made everything more time consuming. "The work that I used to do, involving sheet metal work, most of it was on WhatsApp. I used to send photos to the person who used to make the final material. He used to instantly check it and reply. That instant communication was gone" he said. With a strong customer base in remote places like Gurez and Kupwara, where cellular network connection remains poor even in normal times, Nasir Bukhari would rely on the internet for communication, using WhatsApp or Email: "We lost complete touch with our customers in those areas" he reported after the Internet Shutdown. At the Rangreth Industrial area manufacturers eventually arranged for a dedicated line from a private internet service provider (ISP) but after the killing of Riyaz Naikoo on May 8th 2020, that too was snapped, and was restored only much later.

"Although the government has set up facilitation centres at various places, these are not enough," a businessman told Economic Times. "For example, I have to shut my shop for a day to be able to give GST returns. It is not only cumbersome but humiliating as well."

Filing the complex GST returns is essential for all businesses and only possible through an online portal. Despite the absence of the internet, there was no relaxation on filing GST returns for business, and the government instead announced the setting up of public ‘kiosks’, meant to service students, job applicants, contractors filing tenders and others. "Although the government has set up facilitation centres at various places, these are not enough," a businessman told Economic Times. "For example, I have to shut my shop for a day to be able to give GST returns. It is not only cumbersome but humiliating as well."

"I had to go all the way to Pathankot to file my GST returns. I drove 400 km to Lakhanpur and only when I reached Madhopur, I got internet connection. I parked the car on the side of the road and as soon as I got connected, I did my work," Iqbal Ahmed Ganai told Telephone interview / Iqbal Ahmed Ganai / 24.06.2020JKCCS researchers about his experience of filing his GST. It took him three full days to file it – he spent the nights at Jammu, driving across the border to Madhopur (in Punjab) every morning, and after finishing his internet related work, including filing GST returns and checking emails, returned to Jammu. "The kiosk set up at S.P. College used to get so crowded, the rush was too much. People had to wait for 2-3 days for their turn," Iqbal Ahmed said. He added, "If we only spend time filing GST then when can we do other work?"

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

The nascent Information Technology industry in Kashmir, with an estimated revenue of Rs 4.5-5 billion, and employing 25,000 people across the Valley, was heavily impacted by the shutdown. YSS Microtech Pvt. Ltd., a software development and technology support company lost contact with their clients for almost four months: they eventually forfeited 150 of their 400 hard-won clients. Its founder, Shahid Nazir Shah spoke to Telephone interview / Shahid Nazir Shah / 04.04.2020JKCCS researchers of their venture into Diagnostic Labs. With its heavy dependence on the internet, it had to be wound up after the August 5th shutdown despite the fact that it had several premium clients in Kashmir.